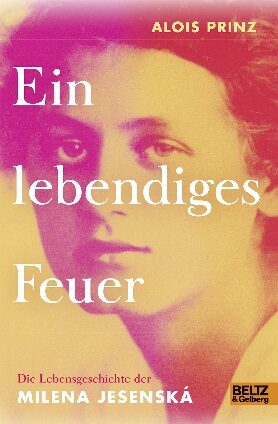

Alois Prinz

Ein lebendiges Feuer. Die Lebensgeschichte der Milena Jesenská

[A Living Fire: The Life Story of Milena Jesenská]

- Beltz & Gelberg Verlag

- Weinheim / Basel 2016

- ISBN 978-3-407-82177-5

- 240 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

So much courage

The romance did not last long, however, because unlike the highly vulnerable writer, who viewed his letters and literature as a refuge, Milena made concrete demands. Two hours of life were worth more to her than two written pages, she answered to him, as Alois Prinz relates in his biography. Milena Jesenská’s post-mortem fame was initially thanks to Kafka scholarship. Kafka’s "Letters to Milena" turned the nonconformist into a literary icon. Even after the end of their romance, Milena and "Frank" – as she like to call him, on account of his almost illegible signature – remained in touch. The writer entrusted his diaries to her, and after his death in June 1924 she wrote a touching obituary. Hence quite a bit of the material on Milena has been preserved because of her proximity to this literary giant, though this Kafka connection and her attendant fame is also a burden, as biographer Alois Prinz repeatedly points out.

Beyond her affair with this writer thirteen years her elder, Milena, who was born in 1896, led a life that was incredibly intense and rich in personal experience, a life that was paradigmatic of the conflict-ridden twentieth century. She belonged to the artistic and intellectual circles of two great cities, made a name for herself as a journalist, explored changing gender relations, talked politics and fought against European fascism.

The literary scholar and philosopher Alois Prinz, who has written biographies on a range of individuals, from Hermann Hesse and Hannah Arendt to Ulrike Meinhof and Saint Paul, seems to have a particular interest in contrarians (his anthology "Rebellious Sons" appeared in 2010). This time he’s chosen an energetic female rebel with his "Life Story of Milena Jesenská," a biography that should be equally informative for young readers and adults alike.

Precise and empathetic, though restrained enough to not be sentimental, Prinz tells the story of the maladjusted daughter of a well-off family. Milena Jesenská not only rebelled against her father, a professor of dentistry; she challenged the conventions of a world in decline, played sports, went hiking, was self-confident and alert, married a Jewish intellectual (much to the ire of her father, a nationalist Czech) and for a while, in her younger years, even became a communist. Just for a while, though, for she soon tired of following the rigid codes of conduct and publication restrictions of her Soviet-oriented comrades.

In a highly accessible and readable way, Prinz’s biography puts Milena Jesenská’s story in the context of her era. The dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the First World War, growing Czech nationalism in Prague, the founding of the republic, the destructive force of Nazism, beyond the border then closer to home – everything that sounds like prosaic history is vividly told in Prinz’s book, against the backdrop of this thrilling life story.

This is particularly true for the final years of this engaged journalist. In 1938, just before the fateful Munich Agreement, she traveled for weeks to the (then still Czech) Sudetenland where she observed the Sudeten German Nazis there and wrote startling reports for her newspaper. In November 1939, once the Nazis had occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia, Milena was arrested for her underground activities. She was acquitted in Dresden but placed in protective custody by the Nazis. Soon afterwards she was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp for women, where she died in 1944.

The letters she wrote from the camp reveal how much she missed her daughter, but also her father and the city of Prague. "In each letter," Prinz explains, "Milena declared how well she was doing and that they had no need to worry about her. This wasn’t true, of course." Yet still she retained her courage and charitable spirit in the camp, as shown by the testimonies of other inmates, who admired her "fearless behavior" until the very end. "She may have lived with careless abandon, but she was always prepared to bear the consequences of her lust for life," writes Alois Prinz in his epilogue. A beautifully told life story that stays with you long after reading.

Translated by David Burnett

By Jutta Person

Jutta Person, born 1971 in South Baden, studied German, Italian and Philosophy in Cologne and Italy, and gained a doctorate with a dissertation on the history of physiognomy in the 19th century. A journalist and cultural commentator, she is based in Berlin and writes for the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Die Zeit and Philosophie Magazin. From 2004 to 2007 she was an editor at Literaturen; since 2011 she has been in charge of the books section at Philosophie Magazin.

(Updated: 2020)

Publisher's Summary

Her brief love affair with the poet Franz Kafka made her world famous. But Milena Jesenská was more than that. A coveted figure in the Prague intellectual scene, she later became a committed political journalist and finally a resistance fighter in the Third Reich.

Milena Jesenská (1896-1944), the daughter of a Prague professor, fought for her independence all her life. She abandoned her medical studies, married against the will of her father who subsequently had her committed to an insane asylum, and developed into a journalist who spoke out against social inequality and battled the Nazi regime.

With great respect and poignancy, Alois Prinz tells about the 24-year-old Milena as her path crossed with Kafka’s. He consults the newly discovered letters that Milena wrote in Ravensbrück to her father and her daughter Honza. The result is the portrait of a unique young woman, passionate in love, friendship and in her concern for others.

(Text: Beltz & Gelberg Verlag)