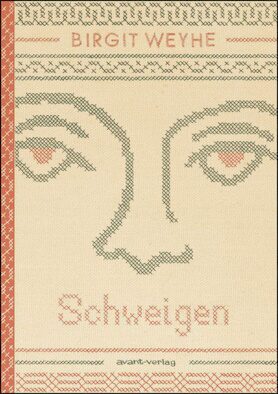

Birgit Weyhe

Schweigen

[Staying silent]

- avant Verlag

- Berlin 2025

- ISBN 978-3-964-45141-5

- 368 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

For this title we provide support for translation into the Polish language (2025 - 2027).

Sample translations

Let us not forget

Birgit Weyhe’s new graphic novel Schweigen (‘Keeping mum’) could equally well be described as a non-fiction comic, for the incidents recounted here are all completely true, as is attested by numerous documents. In her longest work to date Weyhe depicts a continuum stretching from the Nazi era in Germany to Argentina’s military junta.

The illustrator and comic artist Birgit Weyhe was born in Munich in 1969 and grew up in Eastern Africa; she studied Illustration in Hamburg under the well-known artist Anke Feuchtenberger, after first completing a degree in Literature and History. She has been producing graphic novels for almost twenty years now, novels that are devoted to topics that are socially and in most cases also historically highly relevant. Whereas in 2013 in her book Im Himmel ist Jahrmarkt (‘There’s a fairground in heaven’) she chose to write up her own family story, in her subsequent books she has repeatedly devoted herself to biographies that deal in all sorts of different ways with Germany and often also with Africa. Her book Madgermanes (same title in the English edition) concerned the lot of Mozambicans contracted to work in the German Democratic Republic, and was awarded the 2016 Max and Moritz Prize – Germany’s foremost prize for comic books – as the ‘best comic in the German language’.

She wrote numerous short comic-strip biographies of various individuals for the Lebenslinien (‘Life lines’) column run by the Berlin daily newspaper Der Tagesspiegel. Ultimately she developed one of these portraits into her graphic novel Rude Girl, a biography in comic form of the Afro-American German literary scholar Priscilla Layne. She was nominated for the Leipzig Book Fair Prize for this work, and it won her the Hamburg Book Prize. In 2022 Birgit Weyhe was awarded the Max and Moritz Prize as ‘the best creator of comics in the German-speaking lands’.

Her most recent work, Schweigen, reprises numerous themes that Weyhe, now based in Hamburg, had already dealt with in her earlier books, such as the critical reappraisal of Germany’s past; the topics of ‘guilt’ and the Holocaust; the often under-rated role of women within the shadowlands of history. In this new book she explores the links between the fate of German Jews during the nazi era and the lot of victims of Argentina’s military dictatorship. She does this to brilliant effect by recounting in parallel the biographies of Ellen Marx and her daughter Nora on the one hand, and Elisabeth Käsemann on the other.

Both families had their roots in Germany: in May 1939 Ellen Marx fled the pogroms, discrimination and persecution then rampant in Germany in order to live in safety in Argentina. The majority of her family had to stay in Germany and in due course were murdered by the nazis. Elisabeth Käsemann however, born in 1947, grew up in Federal Germany. As a fellow student and friend of Rudi Dutschke she was part of the student movement in the 1960s. She travelled subsequently throughout South America before settling in Argentina to do social work and involve herself in political activism. In 1977 she was murdered in the notorious torture prison of El Vesubio as an ‘opponent of dictatorship’.

Between scenes depicting the protagonists’ lives Weyhe interpolates contextualising chapters conveying a trenchant and well-informed picture of the historical and political landscape of the time. Birgit Weyhe has developed her personal mode of graphic narration in such a way that her simple, ‘flat’ illustrations effectively combine both European and African graphic techniques and thereby enable the reader to directly visualise the thought processes involved. The especially impressive sections of the book are those that convey unspeakably awful events, acts of cruelty and instances of violence, for instance by the use of overpainting, frantic scratchings and scribblings, and patches of black.

The book’s title, Schweigen, refers back to quotations from the famous pair of cultural experts Jan and Aleida Assmann, and highlights the numerous and diverse forms of this kind of human behaviour: staying silent in order to survive; in order to forget traumatic experiences; and not least in order to conceal one’s own guilt and to avoid taking appropriate action. Thus for instance reference is made to the disgraceful role of the German ambassador in Buenos Aires and of the German Schmidt-Genscher government in the 1970s, neither of whom did anything to help these German victims of the military dictatorship at a juncture when it would still have been possible to save them. The reasons for their failure to act lay not least in the then flourishing economic relations between the two countries, which were not to be put in jeopardy.

In order to deal appropriately with her topic Birgit Weyhe read innumerable books and biographies, consulted historians and other experts, visited key locations (including the torture prison El Vesubio near Buenos Aires), and not least of all she also made contact with the Marx and Käsemann families.

In Schweigen Birgit Weyhe succeeds once again in exploiting the possibilities of the medium of the comic in order to tackle highly complex themes in a critical and challenging manner and to present them in pictorial form in original and telling ways. The links and entanglements of German and Argentinian history and politics are revealed soberly but trenchantly. The terrible ordeals endured by individuals that Birgit Weyhe retrieves from virtual obscurity in Schweigen leave us dumbfounded, while simultaneously showing us how societies, governments and justice systems all fell miserably short of what might have been expected of them.

Translated by John Reddick

By Ralph Trommer

Ralph Trommer, Dipl. Animator, is a freelance writer and artist who is a regular contributor of reviews and articles on comics, graphic novels and films for a variety of media.

Publisher's Summary

In most countries people hold their peace after periods of tyranny and suppression - a stance that simultaneously protects the perpetrators, and encourages people to forget the victims and their suffering. The graphic novel Schweigen focuses our minds on the fate of two particular women.

One of them is Ellen Marx, who in early 1939 emigrated to Buenos Aires as a 17-year-old German Jew. Ellen’s entire family perished in the holocaust. Then in the 1970s Ellen’s experience of dictatorship is tragically replicated: her daughter Nora ‘disappears’ during Argentina’s brutal military dictatorship.

The other woman is Elisabeth Käsemann, who belonged to the post-war generation in Germany that became politicised under the aegis of the student movement. In 1969 she went to study in Buenos Aires and involved herself in activities within the poor quarters of the city. In 1977 she was arrested, carted off to the El Vesubio torture camp, and murdered. The German Foreign Office ignored her story, as economic interests and the impending World Football Cup in Argentina were deemed to be more important.

(Text: avant Verlag)