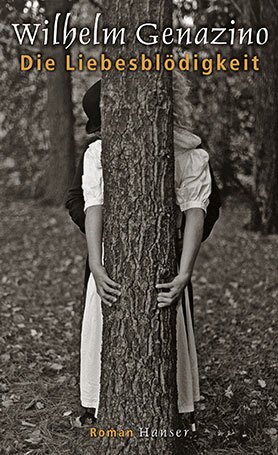

Wilhelm Genazino

Die Liebesblödigkeit

[Lovebefuddled]

- Carl Hanser Verlag

- Munich 2005

- ISBN 3-446-20595-0

- 203 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Wilhelm Genazino

Die Liebesblödigkeit

[Lovebefuddled]

Sample translations

Review

One man, two women, three different apartments – a simple and (at first glance) manageable situation for the nameless hero of Büchner prizewinner Wilhelm Genazino’s latest novel. But however easy it may be to identify the components of this constellation, the tangle of relationships which it creates, and the resulting complex of problems, quickly proves quite complicated: the 52-year-old narrator, a traveling lecturer specializing in the apocalypse of civilization, loves two women and lives his one, disturbingly short life with them in three different apartments, Sandra’s, Judith’s and (rarely) his own – all in proper turn, because the two women do not know about each other.

This is the case even though the narrator’s love affair with these two women has lasted for years, even decades, and he has no plans to change anything. For: “I strongly recommend the lasting love of two women. It is like a double anchoring in the world. (...) I often compare it with filial love. No one ever demanded that we must love only our mother or only our father.”

Thus he loves both the 43-year-old Sandra, the manager’s secretary for a manufacturer of sanitary facilities, practical, considerate and agreeably well-organized (in sexual matters as well), and the 51-year-old Judith, a thwarted concert pianist who supports herself with tutoring and piano lessons, and “devotes herself to art, thought and reflection”. What he loves about Sandra is that she is a “love-tinkerer”, as inventive as she is pragmatic, while Judith allows him to experience an “authenticity” which he misses acutely in his other relationships. With her he can finally stop playing the intellectual who is constantly coming up with new and startling hypotheses about Flaubert, Proust, and the corresponding secondary literature.

As far as he is concerned, this triangle – anything but an ordinary ménage à trios – could go on forever were it not for the symptoms of old age that have recently begun intensifying: varicose veins, cramps in the calves and a nervous twitch in his right eyelid. Above all, the diminishing of his sexual powers forces him to the momentous realization: “There is someone I must come to terms with, and that is myself. I am tormented by the feeling that I am rapidly aging and must put my affairs in order. By that I mean simply and solely my love affairs.”

For the narrator, this realization means that he must relinquish one of the two women: his ultimate fear – that the two unsuspecting women will meet at his sickbed – looms with increasing vividness. But which of the two equally beloved women should he leave for the other? That is the tormenting, unsolvable question that will hound him one hot summer long. He will be granted only a few days’ respite from this conflict, when both women are simultaneously on vacation or visiting relatives.

The sense of being confronted with a life-altering decision, along with the “fear that my desire for order (one Frau, one love, one apartment, one clarity) could destroy both the present order and all future orders”, increasingly paralyzes him. And when Sandra seems likely to catch onto his relationship with Judith, exacerbating the situation still more, he can think of no way out but to confide in the panic counselor Dr. Ostwald.

Doctor Ostwald belongs to the narrator’s peculiar circle of acquaintances, as does the disgust expert Dr. Blaul, the artist Morgenthaler, who has recently started working as representative for the indignant at the Delling Factory, and the post office hater Bausback, who spends his time doggedly and obsessively proving all kinds of errors and sloppiness on the part of the post office. What they all have in common is that they are more or less professionally involved in what the narrator, expert on disaster, diagnoses himself as typical contemporary “deformations which imperceptibly penetrate our lives and gradually suffocate us”. And so our hero – unheroic and even in his own eyes more tragic than anything else – is joined by a cast of other grotesque characters from Genazino’s Frankfurt microcosm, grotesque, yet recognizable in their very exaggeration, who contribute in large part to the charm of this wonderful book and its reading pleasure.

And at the very least the panic counselor Dr. Ostwald seems to know his stuff; with a therapy as simple as it is effective he manages to make the “love-frail man” into a “love survivor” and liberate him from his fear of dying, enabling him ultimately to affirm life in all its disorderliness with a hitherto unknown composure: “I will leave neither Sandra nor Judith, I embrace the confusion and the finality of love life, all will remain as it is and was.”

The entire novel is carried by the laconic cheer and dry self-irony of this final flash of self- and universal knowledge. From the very first line, the felicity, unobtrusive wisdom and poetry of its language wins the reader’s sympathy for this melancholy, middle-aged hypochondriac whose meandering romantic paths and insights of age the reader shares, inspired and exhilarated.

This is the case even though the narrator’s love affair with these two women has lasted for years, even decades, and he has no plans to change anything. For: “I strongly recommend the lasting love of two women. It is like a double anchoring in the world. (...) I often compare it with filial love. No one ever demanded that we must love only our mother or only our father.”

Thus he loves both the 43-year-old Sandra, the manager’s secretary for a manufacturer of sanitary facilities, practical, considerate and agreeably well-organized (in sexual matters as well), and the 51-year-old Judith, a thwarted concert pianist who supports herself with tutoring and piano lessons, and “devotes herself to art, thought and reflection”. What he loves about Sandra is that she is a “love-tinkerer”, as inventive as she is pragmatic, while Judith allows him to experience an “authenticity” which he misses acutely in his other relationships. With her he can finally stop playing the intellectual who is constantly coming up with new and startling hypotheses about Flaubert, Proust, and the corresponding secondary literature.

As far as he is concerned, this triangle – anything but an ordinary ménage à trios – could go on forever were it not for the symptoms of old age that have recently begun intensifying: varicose veins, cramps in the calves and a nervous twitch in his right eyelid. Above all, the diminishing of his sexual powers forces him to the momentous realization: “There is someone I must come to terms with, and that is myself. I am tormented by the feeling that I am rapidly aging and must put my affairs in order. By that I mean simply and solely my love affairs.”

For the narrator, this realization means that he must relinquish one of the two women: his ultimate fear – that the two unsuspecting women will meet at his sickbed – looms with increasing vividness. But which of the two equally beloved women should he leave for the other? That is the tormenting, unsolvable question that will hound him one hot summer long. He will be granted only a few days’ respite from this conflict, when both women are simultaneously on vacation or visiting relatives.

The sense of being confronted with a life-altering decision, along with the “fear that my desire for order (one Frau, one love, one apartment, one clarity) could destroy both the present order and all future orders”, increasingly paralyzes him. And when Sandra seems likely to catch onto his relationship with Judith, exacerbating the situation still more, he can think of no way out but to confide in the panic counselor Dr. Ostwald.

Doctor Ostwald belongs to the narrator’s peculiar circle of acquaintances, as does the disgust expert Dr. Blaul, the artist Morgenthaler, who has recently started working as representative for the indignant at the Delling Factory, and the post office hater Bausback, who spends his time doggedly and obsessively proving all kinds of errors and sloppiness on the part of the post office. What they all have in common is that they are more or less professionally involved in what the narrator, expert on disaster, diagnoses himself as typical contemporary “deformations which imperceptibly penetrate our lives and gradually suffocate us”. And so our hero – unheroic and even in his own eyes more tragic than anything else – is joined by a cast of other grotesque characters from Genazino’s Frankfurt microcosm, grotesque, yet recognizable in their very exaggeration, who contribute in large part to the charm of this wonderful book and its reading pleasure.

And at the very least the panic counselor Dr. Ostwald seems to know his stuff; with a therapy as simple as it is effective he manages to make the “love-frail man” into a “love survivor” and liberate him from his fear of dying, enabling him ultimately to affirm life in all its disorderliness with a hitherto unknown composure: “I will leave neither Sandra nor Judith, I embrace the confusion and the finality of love life, all will remain as it is and was.”

The entire novel is carried by the laconic cheer and dry self-irony of this final flash of self- and universal knowledge. From the very first line, the felicity, unobtrusive wisdom and poetry of its language wins the reader’s sympathy for this melancholy, middle-aged hypochondriac whose meandering romantic paths and insights of age the reader shares, inspired and exhilarated.

Translated by Isabel Fargo Cole

By Anne-Bitt Gerecke