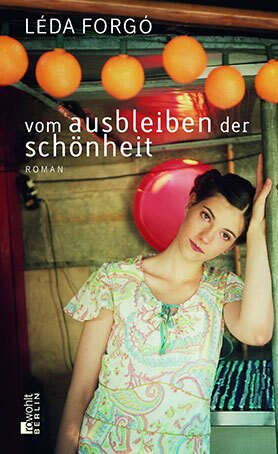

Léda Forgó

Vom Ausbleiben der Schönheit

[The absence of beauty]

- Rowohlt Buchverlag

- Berlin 2010

- ISBN 978-3-871-34676-7

- 256 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Léda Forgó

Vom Ausbleiben der Schönheit

[The absence of beauty]

This book was showcased during the special focus on Spanish: Argentina (2009 - 2011).

Sample translations

Review

Lále’s name isn’t really Lále, her name is Lábán Lenke. In Hungarian Lábán means “on somebody’s leg.” Apart from her mother, nobody has ever called her that. But Lále can’t remember ever having sat on her mother‘s leg, which is why she doesn’t think the name suits her. When Lále moves to Germany, she again is confronted with the question of her name. She considers “Lenke,” but in German the name would constitute a strange blend of three words: „Lenken“(to steer), „Link“(left) and „linkisch“(clumsy), so she decides to continue using the name Lále. Hungarian writer Léda Forgó focuses on identity in this new novel, depicting many aspects of it through her protagonist Lále. In 2008, Forgó was awarded the Adelbert von Chamisso Prize (Förderpreis) for emerging non-German language authors.

Lále moves to Berlin to go to film school and meets a fellow Hungarian named Pável. The two begin a passionate relationship, but he is married with children and refuses to commit himself to her. When Lále becomes pregnant, he urges her to abort the child. Lále is tormented by his suggestion, but ultimately acquiesces. The loss of the child becomes a defining moment in the young woman’s life. When Pável finally separates from Lále, she searches for support and finds it through a dating service. Lále’s third candidate is called Pit, and though they are not entirely compatible, he does correctly answer a question of central importance to her: He wants to have a child with Lále.

At this early point, the trajectory of the novel is clearly delineated. Lále is a delicate and sensitive woman, who is attentive to the world around her. She delicately probes her surroundings and bestows upon them her very personal sense of the abstract notion of “beauty”. Compared to this sensitive woman, Pit comes off as crude, dull and indifferent. The moment she becomes pregnant and her bond to Pit seems indestructible, Láles’ fate is sealed. The story of her misfortune: "the absence of beauty" in her life, follows its inevitable course.

Lále names her son Nathan Bors Lábán, in honor of her Hungarian- Jewish roots. She has to fight Pit’s family to keep the name Nathan; they insist the new family member should be given the very German name "Hermann". Lále desperately tries to create her ideal version of Pit. She persuades him to quit his job at a small company that makes windmills and start his own business. But Pit is not a business man and fails. The unlikely couple gets married so they can be eligible for a bank loan to buy an inexpensive home that needs renovating in Cottbus. The move from Berlin to Cottbus isolates Lále socially. She soon realizes she has not only married the dependent Pit, but also his lower middle class family, whose ways are foreign to her. Communication between them is difficult. "’Oh, Hungary,’ the father remarked as he swallowed the gruesome coffee without flinching, ‘Hungary!' He put the cup down. Lále saw his features twist. ‘Dobri djen!’ He suddenly exclaimed, as though he had suffered a long bout with repression and was now proclaiming democracy. She politely kept quiet, but when the father’s triumphant glare refused to fade, she said, 'That’s not Hungarian.'"

In her new home—the provincial city Cottbus—Pit’s parents come and go as they please, and Lále feels increasingly marginalized. Her marriage to Pit has long since become a union of mutual necessity. Lále often retreats to her "Kreuzberg room”, which is a room in the house that she has decorated with wallpaper, furniture and objects from her years in Berlin. It is the last place of "beauty" in an oppressive environment. But Lále does not give up her struggle for a life that could fulfill her high hopes. She clings to Nathan, her long-awaited and beloved son. She begins a passionate affair with a married woman named Marlis who she has met at Nathan’s nursery school. Hope returns to her otherwise dreary life, until Marlis dies of cancer. When Lále returns to her stifling family situation, she can’t help but notice something has changed: Pit’s family has started scheming against her. One day Pit and Nathan leave home and don’t come back.

Lále’s world collapses. With her last ounce of strength, she pretends to make up with Pit. When Pit and Nathan return, Lále secretly prepares her escape with the boy. She takes her son to Berlin and stays in the scantily furnished apartment of a former lover. Relying solely on her herself and without financial resources, her life grows even lonelier. Nathan also suffers from being separated from his father and their insecure financial situation. He grows up under his distressed mother’s care and without contact to kids his age. Lále can’t turn to any official agency for help- her husband has pressed charges and she is being accused of kidnapping. She gives the case to a young, inexperienced lawyer. During the trial over custody of Nathan, it turns out this, too, was a mistake: She loses her son and ends up back where she started after the abortion at the beginning of the novel: in the void.

It would be easy to read the novel as a story about the failure of a young life. Lále continuously makes wrong decisions. After she loses Pável and their child, she firmly holds on to what she had lost and fails to recognize she cannot find the happiness with Pit that she had been seeking with Pável. She becomes increasingly entangled in untenable constructs: Their son, the marriage, and finally the financial burden caused by the purchase of the house on credit - inevitably the reader is tortured by trying to comprehend Lále’s involvement in the structures that threaten to steal the very air she breathes.

And yet Láles actions are understandable. It is devastatingly clear that her struggle for a happy life actually is a struggle for security and a stable identity. This conflict is clearly the focus of the novel: Lále is half-Jewish, at least that is what she was told; her father was murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Her mother left her at an early age and she grew up with her grandmother. Ultimately, it is this void that Lále seeks to fill with her own child. Her lack of a home is also reflected in her life in Germany. She lives between Hungarian and German languages, oscillates between men and women and between relationships with the two men Pável and Pit, who also ultimately represent two different cultures. Thus, a void is created around Lále, who not only seems to live in a cocoon but also remains at a distance from the world that surrounds her.

The narrative style helps create this impression. The narrator's voice jumps back and forth between the protagonist’s internal and external perspective. She maintains the tension between Lále and her surroundings. She connects and separates the character and her environment as though there was a stretched membrane between them. She consistently uses flashbacks to show us Lále’s past relationship to Pável and makes us vividly aware of her present isolation. Content and language impressively depict a modern woman’s destiny. Nevertheless, we do not only see a flawed life. The story raises the question of what actions are possible for an individual who has had the rug pulled out from under her feet. And it remains open: will Lále perhaps make the right decisions next time?

Lále moves to Berlin to go to film school and meets a fellow Hungarian named Pável. The two begin a passionate relationship, but he is married with children and refuses to commit himself to her. When Lále becomes pregnant, he urges her to abort the child. Lále is tormented by his suggestion, but ultimately acquiesces. The loss of the child becomes a defining moment in the young woman’s life. When Pável finally separates from Lále, she searches for support and finds it through a dating service. Lále’s third candidate is called Pit, and though they are not entirely compatible, he does correctly answer a question of central importance to her: He wants to have a child with Lále.

At this early point, the trajectory of the novel is clearly delineated. Lále is a delicate and sensitive woman, who is attentive to the world around her. She delicately probes her surroundings and bestows upon them her very personal sense of the abstract notion of “beauty”. Compared to this sensitive woman, Pit comes off as crude, dull and indifferent. The moment she becomes pregnant and her bond to Pit seems indestructible, Láles’ fate is sealed. The story of her misfortune: "the absence of beauty" in her life, follows its inevitable course.

Lále names her son Nathan Bors Lábán, in honor of her Hungarian- Jewish roots. She has to fight Pit’s family to keep the name Nathan; they insist the new family member should be given the very German name "Hermann". Lále desperately tries to create her ideal version of Pit. She persuades him to quit his job at a small company that makes windmills and start his own business. But Pit is not a business man and fails. The unlikely couple gets married so they can be eligible for a bank loan to buy an inexpensive home that needs renovating in Cottbus. The move from Berlin to Cottbus isolates Lále socially. She soon realizes she has not only married the dependent Pit, but also his lower middle class family, whose ways are foreign to her. Communication between them is difficult. "’Oh, Hungary,’ the father remarked as he swallowed the gruesome coffee without flinching, ‘Hungary!' He put the cup down. Lále saw his features twist. ‘Dobri djen!’ He suddenly exclaimed, as though he had suffered a long bout with repression and was now proclaiming democracy. She politely kept quiet, but when the father’s triumphant glare refused to fade, she said, 'That’s not Hungarian.'"

In her new home—the provincial city Cottbus—Pit’s parents come and go as they please, and Lále feels increasingly marginalized. Her marriage to Pit has long since become a union of mutual necessity. Lále often retreats to her "Kreuzberg room”, which is a room in the house that she has decorated with wallpaper, furniture and objects from her years in Berlin. It is the last place of "beauty" in an oppressive environment. But Lále does not give up her struggle for a life that could fulfill her high hopes. She clings to Nathan, her long-awaited and beloved son. She begins a passionate affair with a married woman named Marlis who she has met at Nathan’s nursery school. Hope returns to her otherwise dreary life, until Marlis dies of cancer. When Lále returns to her stifling family situation, she can’t help but notice something has changed: Pit’s family has started scheming against her. One day Pit and Nathan leave home and don’t come back.

Lále’s world collapses. With her last ounce of strength, she pretends to make up with Pit. When Pit and Nathan return, Lále secretly prepares her escape with the boy. She takes her son to Berlin and stays in the scantily furnished apartment of a former lover. Relying solely on her herself and without financial resources, her life grows even lonelier. Nathan also suffers from being separated from his father and their insecure financial situation. He grows up under his distressed mother’s care and without contact to kids his age. Lále can’t turn to any official agency for help- her husband has pressed charges and she is being accused of kidnapping. She gives the case to a young, inexperienced lawyer. During the trial over custody of Nathan, it turns out this, too, was a mistake: She loses her son and ends up back where she started after the abortion at the beginning of the novel: in the void.

It would be easy to read the novel as a story about the failure of a young life. Lále continuously makes wrong decisions. After she loses Pável and their child, she firmly holds on to what she had lost and fails to recognize she cannot find the happiness with Pit that she had been seeking with Pável. She becomes increasingly entangled in untenable constructs: Their son, the marriage, and finally the financial burden caused by the purchase of the house on credit - inevitably the reader is tortured by trying to comprehend Lále’s involvement in the structures that threaten to steal the very air she breathes.

And yet Láles actions are understandable. It is devastatingly clear that her struggle for a happy life actually is a struggle for security and a stable identity. This conflict is clearly the focus of the novel: Lále is half-Jewish, at least that is what she was told; her father was murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Her mother left her at an early age and she grew up with her grandmother. Ultimately, it is this void that Lále seeks to fill with her own child. Her lack of a home is also reflected in her life in Germany. She lives between Hungarian and German languages, oscillates between men and women and between relationships with the two men Pável and Pit, who also ultimately represent two different cultures. Thus, a void is created around Lále, who not only seems to live in a cocoon but also remains at a distance from the world that surrounds her.

The narrative style helps create this impression. The narrator's voice jumps back and forth between the protagonist’s internal and external perspective. She maintains the tension between Lále and her surroundings. She connects and separates the character and her environment as though there was a stretched membrane between them. She consistently uses flashbacks to show us Lále’s past relationship to Pável and makes us vividly aware of her present isolation. Content and language impressively depict a modern woman’s destiny. Nevertheless, we do not only see a flawed life. The story raises the question of what actions are possible for an individual who has had the rug pulled out from under her feet. And it remains open: will Lále perhaps make the right decisions next time?

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Eva Kaufmann