Sarah Jäger

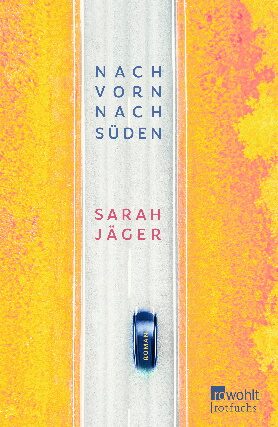

Nach vorn, nach Süden

[Onwards, Southwards]

- Rowohlt Buchverlag

- Reinbek bei Hamburg 2020

- ISBN 978-3-49900-239-7

- 224 Pages

- 13 Suitable for age 14 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Sarah Jäger

Nach vorn, nach Süden

[Onwards, Southwards]

Greek rights already sold

Sample translations

Beyond the horizon - a very special road movie for the cinema of the mind.

Sarah Jäger is completely sure-footed in her milieu; her imagery is completely three-dimensional. Then there's the refreshingly vibrant, sharp dialogue, and the thrillingly dramatic elements. Not to mention the affection which Jäger has for all her characters, even the weird ones. The author takes barrenness and restricted horizons; failure and rebellion; sadness and heartbreak - in particular heartbreak related to love, of course - and manages to turn them all into something full of hope. This presumably has much to do with her talent for approaching the story with an unbiased eye. Her novel is full of wit, irony and warmth as well as 'life wisdom' - bear in mind she worked in a call centre, as a theatre pedagogue, and as a bookseller, so has already had considerable experience of three very different worlds. Throughout the novel, you can sense her joy in throwing ideas up into the air and seeing what happens to them before they land on the page or the computer screen. She approaches the fictive events with articulacy and awe, as if it were the first time she had encountered them. No hint of professional conceit. Just joyful curiosity.

And yet the novel begins with drab greyness, in the back yard of a Penny supermarket branch somewhere in the industrial Ruhr area, where the temps hang out during their breaks. A scene which is replicated in the little concrete sociotopes which we would all recognise: at petrol stations, outside nightclubs, in car-parks, at the foot of monuments, on the steps of launderettes, outside cinemas, and sheltering outside supermarkets. Young people meet, hang out, smoke, drink, perhaps share a joint, and try out their repertoire of young maleness and femaleness. Learning social behaviour with all its colours and shades.

Duck's Arse, the narrator, is on the margins of the Penny clique. This much is immediately clear by the fact that the gang have given her this irrevocable name by which she introduces herself to the reader. She's tolerated, but isn't particularly well liked. However, she is already in her second term of studying German at university and is the only one who has a driving licence. She's no fool, either. She has her eye on talkative joker Can, who is about to struggle his way through his Abitur resits. But he seems to be interested only in the beautiful Marie, saviour of the universe, who has just finished her vocational qualifications. And who, in turn, can't get over being separated from Jo. A collection of more shadowy characters, all aged between 15 and 20, orbit around the main characters. Their good qualities are only very gradually revealed to the readers.

The plot is based around one major event: the sudden disappearance of sixteen year old Jo six months previously. The search for him, which constitutes the main part of the story, begins with an explosive car-share: Can, Marie and Duck's Arse climb into the latter's Corsa and set off to spend the summer holidays looking for Jo. This is the start of a crazy road trip - or road movie, if you switch on the cinema of your mind. The narrator herself can barely believe that she was responsible for coming up with the suggestion which would change her life so dramatically (although she doesn't know this when she suggests it). They set off from the Ruhr heartlands heading for the sticks and Oer-Erkenschwick (just because the place-name makes your tongue turn somersaults! Writer's comment). After Oer-Erkenschwick, there's a kind of vortex of mid-Germany which would swallow them up, and so they return home empty handed. Then they set off again in a slightly different direction, to a punk gig between a cowshed and a field. From there, they carry on - upgraded in transport terms to a band's camper van - to a south German town. From there, they defy expectations by heading not for the cliché-soaked sunny South, but to the rugged North Sea. Always taking the back roads, as Duck's Arse doesn't feel confident on the motorway.

This, then, is the attractive frame within which a portrait of colourful and varied young lives emerges from the confines of a grey back yard. Crazy and touchingly amusing. Life drawing us out into the world so that we get to know ourselves better: this is one of the perennial literary themes. But the notion of Pavel - or, rather "Our Pavel" - building a lookout tower in the back yard out of old wooden pallets in order to broaden the horizons of the Penny clique really deserves to be patented.

Translated by Helena Kirkby

By Siggi Seuß

Siggi Seuß, freelance journalist, radio script writer and translator, has been writing reviews of books for children and young people for many years.

Publisher's Summary

For a group of temporary employees of a local supermarket, the backyard of the discounter is more than meets the eye. It is a break room, a living room and sometimes also a party cellar. In the backyard you get your name, whether you like it or not. If you are lucky, you will be ennobled with an "our", just like “our Pavel”. Or you are unlucky. Like “Duckbutt”. She got her name from Jo, who disappeared months ago. His ex-girlfriend Marie, his best friend Can and the first-person narrator, “Duckbutt”, start looking for Jo and the reasons for his disappearance. Their only clues: stamps on the postcards that he sent to Marie.

The search for him develops into a wild summer trip through roaring hot July days. Without a plan, without air conditioning, further and further south.

(Text: Rowohlt Buchverlag)