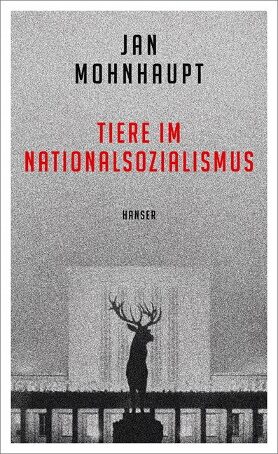

Jan Mohnhaupt

Tiere im Nationalsozialismus

[Animals under National Socialism]

- Hanser Berlin

- Berlin 2020

- ISBN 978-3-446-26404-5

- 256 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Published in Greek with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

The Bellowing of German Red Deer – Jan Mohnhaupt investigates how Nazi ideology was instilled in every sphere of life, encompassing even the treatment of animals

Mohnhaupt explains in his introduction that there have not been many studies on animals in the Nazi era to date, one of the reasons being that in Germany people fear the appearance of minimizing the sufferings of the human victims. But the very fact that the story of the animals would seem so innocuous illustrates the extent to which everyday life in the NS dictatorship was permeated with ideology. In the six chapters that follow this introduction—chapters about dogs, pigs, insects, cats, deer, and horses—Mohnhaupt breaks down the body of National Socialist thought by means of this animal-focused perspective. His vivid account, which offers a rewarding reading experience for the general reader as well as for scholars, lays out the manner in which various facets of Nazi ideology found their way into the everyday lives of farmers, children, and pet owners. Three years earlier, the author of this book, a journalist and writer born in 1983, had published a work of nonfiction that explored the connection between politics and animals. The Zookeepers’ War recounted the history of the two Berlin zoos and their longstanding rivalry in divided Germany. In the National Socialist era, the situation proved to be incomparably more complex, because animals functioned not only as symbols, but also as providers of meat, and in this way were crucial to the war effort.

Let us consider the example of pig breeding: Walther Darré, who held the offices of Reich Farm Leader and Reich Minister of Food and Agriculture, sought to enable the German people to become independent of the need to acquire fat from abroad, and counted on feedlots to achieve national self-sufficiency. At the same time, the pig became the symbol of a doctrine that was fixated on farmlands and fields: “Darré had no misgivings about carrying over to humans the methods of animal breeding that he learned in his studies. His plan was to regenerate the Aryan race with the farm as a basis,” Mohnhaupt writes. Pig breeding was also put to ideologically useful purposes: “For Darré, the pig was the Leitrasse (guiding species) of the Nordic peoples, and brought the Teutonic forebears to become settled in one place.”

As the six chapters of this volume impressively substantiate, those who speak in terms of “master humans” are bound to invent “master animals” as well. The supposedly impressive modern laws to protect nature and animals, which had initially been enacted to outlaw Jewish slaughtering practices, did not apply equally to all animals. Hunting rituals and the manner in which wildlife was treated also provide fitting illustrations of how interest-driven and spurious the idea behind Nazi animal protection actually was. Mohnhaupt writes about Hermann Göring, the “Reich Master of the Hunt” and the nation’s “second in command”: “For Göring, nature conservation meant first and foremost the safeguarding of his hunting grounds. And his deer were his top priority. Even though several subspecies of the red deer lived everywhere throughout Europe, from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean region, the sole name for this animal in the ‘Third Reich’ was the ‘German red deer’.”

The only animal that might be considered even more German than the red deer would be the German shepherd, whose life, actions, and impact Mohnhaupt describes in detail. At times the book carries elements of a horror story, such as the author’s depiction of Hitler’s last German shepherd, Blondi. Hitler’s decision, in late April 1945, to try out the deadly effect of cyanide capsules on his supposedly beloved dog makes clear his true attitude toward animals—his purported love of which he had exploited for propagandistic purposes. The Führer may have been a vegetarian who despised hunting, but he was unlikely to have been an animal lover, Mohnhaupt maintains. If we leave aside the instance of Hitler’s last dog, the history of the German shepherd is of interest primarily because it illustrates how the issue of breeding became a focus of attention.

Mohnhaupt sums up the situation as follows: “An ideology that measures the worth of a life by the ‘use’ it provides to its own community does not distinguish between ‘human’ and ‘animal,’ but between life that is ‘useful’ and life that is ‘unworthy of living.’ It consequently arose from the same ideological spirit that afforded some animals special protection while declaring some people ‘parasites’ in turn, and systematically exterminating them.” The analyses of these animals in Mohnhaupt’s book clearly and unmistakably establish how the categories of usefulness und harmfulness came gradually to permeate thinking as a whole. The actions of sorting out and destroying came to the fore, interlaced with a fixation on breeding and on racial fanaticism, from potato beetles, which were branded the enemy, to the extinct aurochs, which were venerated with cultish fervor.

Translated by Shelley Frisch

By Jutta Person

Jutta Person, born 1971 in South Baden, studied German, Italian and Philosophy in Cologne and Italy, and gained a doctorate with a dissertation on the history of physiognomy in the 19th century. A journalist and cultural commentator, she is based in Berlin and writes for the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Die Zeit and Philosophie Magazin. From 2004 to 2007 she was an editor at Literaturen; since 2011 she has been in charge of the books section at Philosophie Magazin.

(Updated: 2020)

Publisher's Summary

Potato beetles as weapons of war and pigs for educating the masses – under National Socialism, animals weren’t exempt from (mis)appropriation. Jan Mohnhaupt tells their stories vividly and with an eye for everyday detail.

Dog breeding served the Nazis as a model for their racial fanaticism. In primary school, insects were used to prepare children for war. And the stag was used to buttress the myth of the “German forest”. Mohnhaupt discovers animals and their unique role in National Socialism in diaries and specialist journals, school textbooks and propaganda material. In the style of a historical reportage, he follows in their footsteps, from horses on the Eastern Front to cats in German living rooms. And he makes clear: “The Nazi perspective on the world is reflected with surprising clarity even in this aspect of the Third Reich.”

(Text: Hanser Berlin)