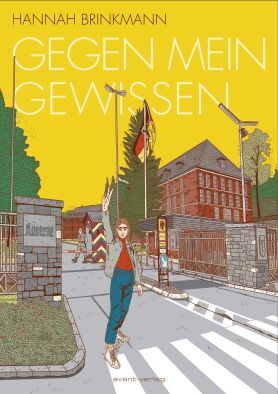

Hannah Brinkmann

Gegen mein Gewissen

[Against my conscience]

- avant Verlag

- Berlin 2020

- ISBN 978-3-96445-040-1

- 232 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

For this title we provide support for translation into the Greek language (2019 - 2021).

More

Sample translations

Hermann’s Story. Hannah Brinkmann’s graphic novel Gegen mein Gewissen

When the new West German state was established in 1949 there appeared to be nothing contentious about Article 3, Paragraph 4 of the ‘Basic Law’: ‘No person shall be compelled against his conscience to render military service involving the use of arms’; after the human tragedy of Nazism and the Second World War, who could even begin to contemplate the idea of reintroducing conscription? Seven years later, however, politics were dominated by the Cold War. Rearmament was in full swing, and the declaration in the Basic Law was farcically reinterpreted. Young men who objected to military service had to subject themselves to an examination of their conscience by an assessment panel administered by the Ministry of Defence itself – as though it were possible within a single hour of often highly aggressive questioning for the chief assessors and their honorary co-assessors to arrive at a considered judgment regarding the alleged pains of conscience of the applicant before them. In 1972 there were slightly under 30,000 conscientious objectors in the Federal Republic. More than 11,000 were approved following their initial appearance before the panel, but those who were turned down found themselves subjected to a long-drawn-out process that by no means always culminated in success. Those who despite rejection of their bid for exemption refused to serve under arms were prosecuted as criminals. Many conscientious objectors lost all faith in justice and the law during this period. In addition, they were vilified as cowards, traitors and ‘pussies’, even though community service - the obligatory substitute for military service - was often far more arduous than its alternative. Quite a few young men went completely to pieces under the relentless pressure of this systematic discrimination in both the private and public domains.

In this reviewer’s experience no other graphic novel has captured this discriminatory environment of the early 1970s as accurately, sensitively and realistically in both word and image as Hannah Brinkmann. Over more than 230 pages she recounts the story of her uncle Hermann, who took his own life in 1973. A dedicated pacifist, he saw no alternative following the dismissal of his conscientious objection and the refusal by the authorities to acknowledge the depressive state that he suffered as a result. Hannah Brinkmann’s family only told her the true facts behind the tragedy once she had reached adulthood. In her Afterword she writes: ‘Hermann’s story became my own. I could move on in my life only by recounting it.’

Hannah Brinkmann takes her readers on an absorbing journey back through time to the Federal Republic of the 1960s and 1970s by means of a captivating combination of narration, ligne claire drawings and surreal picture-sequences. Using painfully clear images with numerous shifts of perspective, she tellingly evokes the milieu in which Hermann grew up - that of a well-to-do Protestant family in North Germany: five siblings; the father a dentist and passionate huntsman; their house stuffed with hunting trophies that inspired fear in Hermann even as a little boy; the whole family and household kept together by a devotedly caring mother prone to closing her eyes to reality. Religious rituals played a central role, though most of the children increasingly took to rebelling against the family’s patriarchal pattern of life.

Hermann developed into a pacifist in this environment, and by way of a contrast to its orderliness and often sterile cleanliness Hannah Brinkmann presents various surreal images that reflect the young man’s inner imaginings and anxieties. She then also relates these fearful imaginings to actual historical events which she evokes in a realistic, quasi-documentary style, before finally offering a kind of family-photo-album review of the happier moments in Hermann’s short life.

There is consolation of a kind in the end: Hermann Brinkmann’s suicide triggered a political debate about the rightness or otherwise of the assessment process in respect of conscientious objectors; it was abolished in 1977.

Translated by John Reddick

By Siggi Seuß

Siggi Seuß, freelance journalist, radio script writer and translator, has been writing reviews of books for children and young people for many years.

Publisher's Summary

‘No person shall be compelled against his conscience to render military service involving the use of arms.’ (Article 4, Paragraph 3 of the Basic Law)

Less than ten years after the Second World War the Federal Republic of Germany had once again come to regard itself as a military power. The Bundeswehr, established anew in 1956, obliged generations of young men to serve under arms. The Basic Law provided for individuals to refuse military service on the grounds of conscience, but even as late as Willy Brandt’s chancellorship such refusals were viewed as a threat to the system.

Individuals were subjected to immense pressure and numerous humiliations when seeking to prove the validity of their conscientious objections – to appraisers to whom the institution of the Bundeswehr was more important than the wellbeing of recruits. One of these young men was Hermann Brinkmann, a staunch pacifist, who was called up in 1973. He tried in vain to oppose the order to join up - and took his own life in the course of basic training...

In Gegen mein Gewissen (‘Against my conscience’) - her first such book, nominated for the Leibinger Prize (Comic Book Prize) - Hannah Brinkmann takes a close look at her uncle’s fate, which hit the headlines right across the country in the 1970s and triggered a debate on the legality of challenging pleas of conscience. Basing herself on calmly conducted, sensitive and brilliant research, this comic-book artist from Hamburg recounts a story of a rebellion against authority and a struggle for what is right.

(Text: avant Verlag)