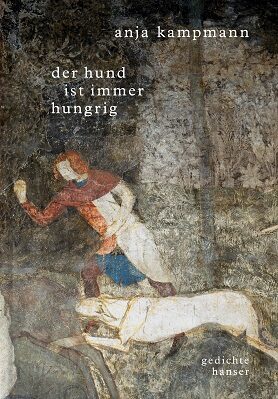

Anja Kampmann

der hund ist immer hungrig

[the dog is always hungry]

- Carl Hanser Verlag

- Munich 2021

- ISBN 978-3-446-26753-4

- 120 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Published in Italian with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

Sleeping dogs in the anthropocene

Anja Kampmann, born in Hamburg in 1983 and now based in Leipzig, came blazing into the world of contemporary German literature like a shooting star. Her debut publication in 2016, the poetry collection Proben von Stein und Licht (‘Samples of stone and light’), attracted much attention; two years later came a novel, Wie hoch die Wasser steigen, the American edition of which (High as the Waters Rise) made it onto the shortlist for the National Book Award. In Germany too she has received numerous awards and prize nominations, and is represented in all the major anthologies of contemporary German poetry.

A significant number of Kampmann’s new poems could be described as obituaries to nature as more and more of it is lost. She focuses on the ubiquitous traces that human beings have inflicted on the planet, on the depredations, spectacular and insidious alike, of the anthropocene era. She writes about cloned animals and Chinese gene experiments, waste products and asphalt, industrial parks and erosion zones, chemical pollution from factories along the Danube, the slaughter of bats by the rotor blades of wind turbines, the relentless retreat of perma-frost, unsuspecting dogs asleep at petrol stations, and campaigns to get rid of moles. She also writes about places she knew during her childhood and youth in the fog-bound north of Germany, where she not only finds personal memories, none of them the least bit idyllic, but also reminders of German war crimes.

Kampmann sticks resolutely to observation and depiction, and never slips into analysis, polemics or moralising. Distanced but never without empathy, her perspective is characterised by a cool melancholy, and in its manner of dwelling on apocalyptic events it evinces a special kind of beauty, an aesthetic at once austere and calm that makes the terror accessible to us without at the same time diminishing its impact. It could serve as a kind of political poetry well suited to our age: it does not agitate, it simply bids us see, and its restrained, almost parenthetic air of disapprobation brings the extent of the devastation home to us more powerfully than strident recriminations could do in our current circumstances.

These poems seem predestined for translation into other langugaes, as they dispense with rhyme, metre and other formal poetic effects, and rely instead on the expressive force of the imagery and the associative potential of the words. They thus amount to a kind of prose poetry with their sometimes fractured syntax and their organic rather than formalistic line breaks, together with a total avoidance of capitalisation and near-total avoidance of punctuation. Both their matter and their mood will surely lend themselves to translation into any language whatever without suffering the slightest diminution of their impact.

Translated by John Reddick

By Kristina Maidt-Zinke

Kristina Maidt-Zinke is a book and music critic at the Süddeutsche Zeitung and also writes reviews for Die Zeit.

Publisher's Summary

Newspaper boys, a girl on a playground, youths with their naive dreams and blue eyeliner – ultimately everyone who drifts or sways through life – all wonder about the bigger picture.

Anja Kampmann shot to fame with two books: her first novel Wie hoch die Wasser stiegen (High as the Waters Rise), and her poetry collection, Proben von Stein und Licht. “Rarely do poets’ first collections come across as finished and laconic as this one, with a sure feeling that beauty often gets in the way of truth”, wrote Paul Jandl in the magazine Literarische Welt.

Anja Kampmann’s new poems are more conscious of form than her previous ones yet also more playful and open; they conjure up marshland, make figures appear and their recurring motifs link the collection together to form a panorama of our times. They confirm Anja Kampmann’s reputation as an independent, unusual voice of her generation.

(Text: Carl Hanser Verlag)