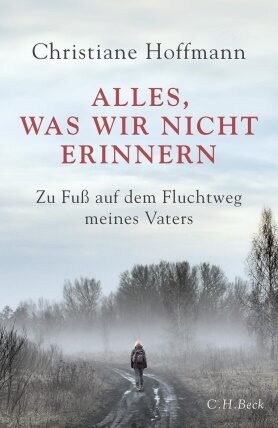

Christiane Hoffmann

Alles, was wir nicht erinnern. Zu Fuß auf dem Fluchtweg meines Vaters

[All the things we no longer remember. Retracing the steps of my fleeing father]

- C.H.Beck Verlag

- Munich 2022

- ISBN 978-3-40678-493-4

- 279 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

History wars and the trauma of flight

Its departure point is the flight of a nine-year-old boy from his home village - then in Silesia, now in Poland. That boy was Christiane Hoffmann’s father. Now, many decades later, his daughter sets out to retrace his escape route: almost 500 kilometres through storms and wintry cold, through marsh and moor, all the way from Rosenthal in Silesia to the Eger region in Bohemia, and subsequently on to Wedel in Schleswig-Holstein. This odyssey was barely ever mentioned again within the family - as was commonly the case amongst the war generation: ‘They don’t complain about what they suffered at the hands of others; that way they don’t have to speak about what they themselves had done. “We paid the price, so everything’s okay now and we just have to move on”.’ But of course everything wasn’t okay. The trauma of their flight was never worked through but simply buried away, only to surface once again in their daughter, born 1967, in the form of nightmares. She is haunted by two recurrent visions - of people desperately packing their suitcases, and people fleeing for their lives.

Come to that, things were also by no means ‘okay’ for the family that took over the Hoffmanns’ farm in 1945. The new inhabitants of Rosenthal had been subjected to forced labour in a German jam factory and on their release were informed that their entire village in West Ukraine had been relocated to Silesia - and thus they now found themselves compelled to accept Rosenthal as their new ‘home’. This one event, though small enough in itself, demonstrates to the reader the far-reaching historical impact of Polish/Ukrainian relations. It gives us an insight into just how intertwined were the destinies of all those who became victims of the twentieth century’s geopolitical upheavals.

For the Hoffmanns it was ‘the Russians’ who were the terrifying bogy-men - and it was precisely Russia that then exercised a magnetic attraction for the Hoffmanns’ daughter once she left school. Christiane learnt her enemy’s language - taught to her, incidentally, by the renowned Dostoievsky translator Svetlana Geier; she moved to Moscow; she married there. Years later she asks herself why she had spent more than forty years being so obsessed by the lands to the east. What lay behind her obsession? The giveaway is a sentence she addresses to her parents: ‘I am ill with home-sickness, a form of homesickness you never felt.’ So this is what lies at the heart of this book: the urge to return to the source of her affliction, to confront her grief at long last and thereby cast off the family curse.

When Christiane Hoffmann submitted the final proofs of her book she could have had no inkling of the forthcoming war in Ukraine - but with its central theme of ‘flight’ the book is eerily relevant to the present situation. Flight as a lived reality; and flight as an experience that goes on inflicting damage on generation after generation. In order to offer an even deeper, more detailed perspective the author doesn’t restrict herself solely to her own family, but as she walks she also provides a running commentary on the situation in the Polish and Czech provinces, where she encounters irredentist ethnic Germans as well as affable Europe-haters, resigned curators of ‘homeland’ museums, and young people fully committed to Project Europe. Overall, however, the picture is one of complex fracture. Disinformation and ancient resentments are what chiefly make it difficult to sell the idea of a flourishing political landscape in Europe. As Hoffmann remarks at one point: ‘Where is Europe supposed to find the strength to put all these things to rights?’

At the stylistic level, too, the book is an impressive success. It is presented over considerable stretches as a letter to her late father, who died in 2018. The poignant tone of the intimate outpourings of a daughter thus alternates throughout with the factual tenor of seasoned journalist Christiane Hoffmann’s accounts of her experiences on the road. She guides her readers with a sure hand through an ideological minefield. Surfing the channels in a Polish hotel early in 2020 she lands on a Russian talk show where there is discussion first of a new mutation of the corona virus, then of a mutation within the political realm that is evidently regarded as far more dangerous. This particular mutation had been unleashed by the President of Ukraine and - so the argument goes - must be eradicated as quickly as possible. He had dared to voice criticism of the Hitler-Stalin pact. ‘They want to rob us of our victory, one of the emblems of our national pride’, fumes the programme; ‘They’re getting too excited; they all share the same view, but they shout and scream all the same as if someone were constantly contradicting them.’

Current circumstances lend this richly layered book of remembrance a tremendous urgency. For Christiane Hoffmann brings to light not only the repressed pain of her own family, but the pain of an entire region. She is talking here about the ‘history war’ that has long been raging on the other side of the Oder. She argues that this war is not about the guilt of the Germans, who have long since owned up to their misdeeds, but about ‘apportioning all the rest of the blame’. Anyone keeping track of current news today knows that Christiane Hoffmann’s diagnosis is absolutely right. One can only hope that her book reaches the widest possible audience, for its double focus on both the personal and the historical makes it an important contribution to our understanding of the political realities of today.

Translated by John Reddick

By Katharina Teutsch

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic. She writes for newspapers and magazines such as: the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Tagesspiegel, die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and for Deutschlandradio Kultur.

Publisher's Summary

"It is the certainty that you can lose everything from one day to the next, your house and farm, your sons, brothers, and parents, your home and even your memory." "On foot?" "On foot." "Alone?" "Alone." – on January 22, 2020, Christiane Hoffmann sets off on her journey from a village in Lower Silesia. She walks 550 kilometers west; it is the route that her father took as he fled from the Red Army in the winter of 1945. His escape and the loss of his home shaped the author's childhood and remained a wound, as in so many other families as well. After the death of her father, she returns to Rosenthal, which is now called Rózyna. She is searching for the story and its scars. She walks the accursed twentieth century out of herself.

Germany in the 1970s: Children are sitting under a table. Above them the adults are sighing, eating canapés, and talking about their lost homeland. They transmit their injuries and nightmares to the next generation. What remains today of the fates of those who fled? How do families, how do societies, Germans, Poles, and Czechs deal with it? On her journey, Christiane Hoffmann is looking for the presence of the past. She struggles through hailstorms and swampy forests. She sits in churches, kitchens, and living rooms. She talks – with other people and with herself. Her book translates recollections of fleeing and being deported into the twenty-first century and warns readers of the horrors of war. It interweaves her family story with history, eyewitness accounts with the encounters she has on her journey. But above all it is a very personal book written in a literary language, a search for a father and his history.

(Text: C.H.Beck Verlag)