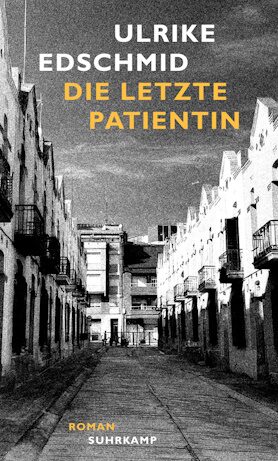

Ulrike Edschmid

Die letzte Patientin

[The Last Patient]

- Suhrkamp Verlag

- Berlin 2024

- ISBN 978-3-518-43183-2

- 111 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

For this title we provide support for translation into the Polish language (2025 - 2027).

Sample translations

On the fault lines of history

The same is true of her latest work, “The Last Patient,” a slender, intense book of only 111 pages – a biography in excerpts, an attempt to tease out the essence of a life, to capture and record something, in dense, lucid prose with no direct speech; a haunting, moving and unsentimental book.

Edschmid tells the story of a young woman from Luxembourg who moves into a shared apartment in Frankfurt in the early 1970s, becoming friends with the first-person narrator. Later in life they keep in touch, when “she,” the unnamed friend, goes on a trip around the world, eventually settling in Barcelona to work as a trauma therapist. For forty years they write letters and visit each other, until the girlfriend’s passing.

As in her other books, Ulrike Edschmid narrates through historical time, along the fault lines of history. Political events reverberate in the background as she builds up her story in the foreground. Her book “A Man Who Falls” (2017), for example, is ostensibly about her partner becoming a paraplegic after he falls from a ladder, and the subsequent slowing down of their daily lives. But it’s also a portrait of West Berlin, about the changes taking place there since the 1980s, as seen from an apartment in a corner building in the neighborhood of Charlottenburg.

“The Last Patient” offers us flashes of the highly politicized environment the author lived in for a while. Already in the second chapter we read, “One night, when our apartment is raided, she stands before the armed policemen in a flowered children’s nightgown made of flannel,” stands “with outstretched arms, before the door of the children’s room in which my son is sleeping.”

Many of Edschmid’s books are about the student movement, about politicization and radicalization. “Woman with a Gun: Two Stories of Terrorist Times” (1996), for instance, depicts the lives of activists Astrid Proll and Katharina de Fries. “The Disappearance of Philip S.” (2013) is an attempt to narrate the life of her on-and-off romantic partner Philip Sauber, who joined the leftwing extremist “June 2nd Movement” and was killed in a shootout with the police in 1975.

The biographies Edschmid unfolds in her books often have something exemplary about them. Indeed, the life her girlfriend lived would have likely been impossible a generation earlier: unmarried, no steady relationship, no kids, lengthy periods of unemployment, traveling the world alone – a woman whose story is representative for an entire generation of women who could suddenly live their lives differently than before.

In the present book, the first-person narrator stays in the background as she relates the other woman’s story. Picking up the letters of her friend, she recounts the latter’s lengthy trip through South America and the United States. She talks about her friend’s inner turmoil, her melancholy and restlessness. There is something raging inside this woman, a burden from the past, her parents’ expectations. And so she lives the life of a drifter, traveling through Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, Brazil, Costa Rica, Panama, Columbia, a courageous woman who hitchhikes alone, is raped, moves on. She seeks a resting place in men, but again and again the relationships fail.

In the second part of the book the girlfriend settles down and becomes a therapist. A young woman comes to her as a patient. Though deeply traumatized, she refuses to speak; for years, each week, she sits with her therapist and doesn’t say a word. The therapist would prefer to be rid of this woman, her leaden silence is simply too burdensome, and she herself is tired, is burdened by her own battle with cancer. But at some point these two women’s lives become inextricably intertwined. Who’s the therapist, who’s the patient? – the question is suddenly no longer relevant. What began as a professional relationship is now a private, familial one.

Edschmid addresses important questions: What remains of a life? Who, if not yourself, will record its most vivid episodes? What is a successful life, what is family? How close can we ever get to others? And how do we find words for our traumas? Edschmid’s novel is a slender but weighty book that stays with the reader long after she puts it down.

Translated by David Burnett

By Anne-Dore Krohn

Anne-Dore Krohn is a literary editor at rbb (Radio Berlin-Brandenburg). She has served in numerous prize juries and frequently acts as a moderator at readings.

Publisher's Summary

A story that encapsulates the restlessness and search for meaning of an entire generation.

She sat at the kitchen table, smoking, exuding a »seductive world-weariness reminiscent of the films of the Nouvelle Vague«. Having been left by a man, she turns up in the narrator’s share house in Frankfurt in 1973 looking for a room. She was majoring in history and French. Three years later, after falling in love with a Spanish anarchist, she follows him to Barcelona.

After a few more abortive relationships, she leaves Europe for the Americas, with stints in Arizona, Mexico City, Guatemala, Buenos Aires, but after years of a peripatetic life and countless »desperate attempts at love«, she finally finds her way back to Barcelona, where she trains to become a psychotherapist, specialising in trauma.

One day, a young woman arrives at her practice who doesn’t speak. Years go by before the first words escape her lips. Has she been the victim of some horrible crime? Or is the darkness that leaves her mute the product of psychosis? What’s clear is that this patient will give her therapist – now gravely ill with cancer – the love she couldn’t find anywhere else in the world.

Ulrike Edschmid tells this moving, disturbing, and ultimately consoling story as is customary for her work: concise and sparse, delivering a dense book that retains a remarkable deftness of touch.

(Text: Suhrkamp Verlag)