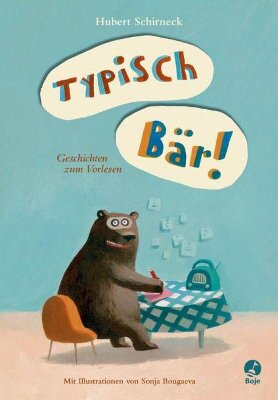

Hubert SchirneckSonja Bougaeva

Typisch Bär!

[Typical bear!]

- Boje Verlag in der Bastei Lübbe GmbH & Co. KG

- Cologne 2012

- ISBN 978-3-414-82294-9

- 120 Pages

- 5 Suitable for age 6 and above

- Publisher’s contact details

Published in Russian with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

Review

The bear likes listening to the radio. In the process he picks up all kinds of information. He finds proverbs especially fascinating. He writes them down, but takes such a long time doing so that by the time he puts pencil to paper he has already forgotten part of the relevant proverb. New ‘proverbs’ thus come into being: ‘Ein Übel kommt selten allein’ (‘Misfortunes seldom come alone’) becomes ‘Ein Apfel kommt selten allein’ (‘Apples seldom come alone’); ‘Morgen ist auch noch ein Tag’ (‘Tomorrow is another day’) becomes ‘Morgen isst auch noch ein Tag’ (‘Tomorrow eats another day’).

The fact that his zany versions of the sayings are devoid of sense or coherence is completely lost on the bear — but not on his neighbours, the duck and his best friend, the lion. There’s no telling him, however, as he is so blissfully certain that he’s got it right, so the other animals simply shake their heads and sigh ‘Typical bear!’

These new stories for reading aloud by Hubert Schirneck turn out to be lovingly ironic tales that are often more ingenious in their development than their simple-sounding title might lead one to suppose. Thus the first story demonstrates right away that half-baked knowledge parroted from the radio does not make anyone truly clever. Again and again, the pieces of information that the bear enjoys listening to on his radio turn out to be seriously defective. It falls to the lion, and especially the lion’s friend Luise, to put him right.

Again and again, Hubert Schirneck has the lion call the bear’s claims into question, for he has made appropriate enquiries, and he knows that the bear’s proverbs don’t actually exist as such. Thus we see analytical thinking and the educative process in action.

Hubert Schirneck writes wonderfully clear prose in this book, prose that is well suited to being read aloud since the sentences are purposefully formulated and devoid of frills. What we see here is a writer operating with great sensitivity in a language world that is readily accessible to six-year-olds, yet at the same time full of charm — all the more so in that Schirneck manages in the numerous dialogues to give unmistakably distinctive voices to the bear and the lion.

Language is the real subject matter of these tales. Thus for instance Schirneck gives his readers some idea of how to handle metaphors by putting together a story about constellations. The bear aims to remove a constellation from the heavenly firmament and pin it to his wall. In the process he falls into a bear-trap, and looking up from the dark pit he suddenly discovers the constellations in the star-lit sky. The fact that no teacherly finger needs to be wagged here derives from Schirneck’s unwavering focus on developing his stories and steering them towards their clear-cut conclusion.

For Schirneck, taking metaphors and similar expressions literally is an approach that shows due respect for the child’s own perspective whilst also lending it an element of poetic comedy. Thus for instance the bear tries to discover what revenge is, since revenge is notoriously said to be sweet — and he is deeply interested in all things sweet. But instead of leading him into dramatic conflicts, this tale leads him into the arms of a lady bear; he duly falls for her, and the whole of the rest of the book is suffused with his longing for this highly agreeable girl-friend.

Schirneck never loses sight of the fact that he is writing for children. He carefully avoids the bleeding heart romances that far too often turn up in children’s literature in defiance of the fact that children of primary school age can’t really make anything much of ‘lurve’ — a phenomenon that is largely incomprehensible to them.

As he awaits the return of his girl-friend the bear begins to brood on things, and finds himself being ticked off by the lion. But the bear is sure of himself in this respect, and retorts that ‘people who brood have ideas, and ideas are a good thing’. He is quite right.

Hubert Schirneck doesn’t portray his bear as a ponderous sort: in full accord with traditional animal symbolism, which attributes energy and creativity to bears, this particular one has huge potential in terms of both imagination and the thirst for knowledge. What’s more, he is a spectacled bear, a fact that Sonja Bougaeva emphasises in her illustrations by a band of white across his face. The eyes are the key focal points in her animal drawings: they routinely convey a slight air of astonishment, and as such are clearly on the lookout for answers.

Hubert Schirneck encourages his readers to listen carefully and to ask questions — but he doesn’t bore them with instant answers. It’s an essential part of language to explore meanings and to experiment with them — a game that is entitled to enter the realms of nonsense now and again. Language is not only an instrument for the acquisition of knowledge: it is also a tool by means of which things in general can be brought into a state of equilibrium.

Hubert Schirneck thus manages to create animal stories that are gentle, funny and thought-provoking, but which at the same time surreptitiously offer a marvellous introduction to the magical realms of language. Anyone who has these tales read to them and is free to ask questions about them as and when they like is certainly going to be well equipped to deal with all the things that have to be learnt within the context of school.

The fact that his zany versions of the sayings are devoid of sense or coherence is completely lost on the bear — but not on his neighbours, the duck and his best friend, the lion. There’s no telling him, however, as he is so blissfully certain that he’s got it right, so the other animals simply shake their heads and sigh ‘Typical bear!’

These new stories for reading aloud by Hubert Schirneck turn out to be lovingly ironic tales that are often more ingenious in their development than their simple-sounding title might lead one to suppose. Thus the first story demonstrates right away that half-baked knowledge parroted from the radio does not make anyone truly clever. Again and again, the pieces of information that the bear enjoys listening to on his radio turn out to be seriously defective. It falls to the lion, and especially the lion’s friend Luise, to put him right.

Again and again, Hubert Schirneck has the lion call the bear’s claims into question, for he has made appropriate enquiries, and he knows that the bear’s proverbs don’t actually exist as such. Thus we see analytical thinking and the educative process in action.

Hubert Schirneck writes wonderfully clear prose in this book, prose that is well suited to being read aloud since the sentences are purposefully formulated and devoid of frills. What we see here is a writer operating with great sensitivity in a language world that is readily accessible to six-year-olds, yet at the same time full of charm — all the more so in that Schirneck manages in the numerous dialogues to give unmistakably distinctive voices to the bear and the lion.

Language is the real subject matter of these tales. Thus for instance Schirneck gives his readers some idea of how to handle metaphors by putting together a story about constellations. The bear aims to remove a constellation from the heavenly firmament and pin it to his wall. In the process he falls into a bear-trap, and looking up from the dark pit he suddenly discovers the constellations in the star-lit sky. The fact that no teacherly finger needs to be wagged here derives from Schirneck’s unwavering focus on developing his stories and steering them towards their clear-cut conclusion.

For Schirneck, taking metaphors and similar expressions literally is an approach that shows due respect for the child’s own perspective whilst also lending it an element of poetic comedy. Thus for instance the bear tries to discover what revenge is, since revenge is notoriously said to be sweet — and he is deeply interested in all things sweet. But instead of leading him into dramatic conflicts, this tale leads him into the arms of a lady bear; he duly falls for her, and the whole of the rest of the book is suffused with his longing for this highly agreeable girl-friend.

Schirneck never loses sight of the fact that he is writing for children. He carefully avoids the bleeding heart romances that far too often turn up in children’s literature in defiance of the fact that children of primary school age can’t really make anything much of ‘lurve’ — a phenomenon that is largely incomprehensible to them.

As he awaits the return of his girl-friend the bear begins to brood on things, and finds himself being ticked off by the lion. But the bear is sure of himself in this respect, and retorts that ‘people who brood have ideas, and ideas are a good thing’. He is quite right.

Hubert Schirneck doesn’t portray his bear as a ponderous sort: in full accord with traditional animal symbolism, which attributes energy and creativity to bears, this particular one has huge potential in terms of both imagination and the thirst for knowledge. What’s more, he is a spectacled bear, a fact that Sonja Bougaeva emphasises in her illustrations by a band of white across his face. The eyes are the key focal points in her animal drawings: they routinely convey a slight air of astonishment, and as such are clearly on the lookout for answers.

Hubert Schirneck encourages his readers to listen carefully and to ask questions — but he doesn’t bore them with instant answers. It’s an essential part of language to explore meanings and to experiment with them — a game that is entitled to enter the realms of nonsense now and again. Language is not only an instrument for the acquisition of knowledge: it is also a tool by means of which things in general can be brought into a state of equilibrium.

Hubert Schirneck thus manages to create animal stories that are gentle, funny and thought-provoking, but which at the same time surreptitiously offer a marvellous introduction to the magical realms of language. Anyone who has these tales read to them and is free to ask questions about them as and when they like is certainly going to be well equipped to deal with all the things that have to be learnt within the context of school.

Translated by John Reddick

By Thomas Linden

Thomas Linden is a journalist (Kölnische Rundschau, WWW.CHOICES.DE) specializing in the areas of literature, theater and film. He also curates exhibitions on photography and picture book illustration.