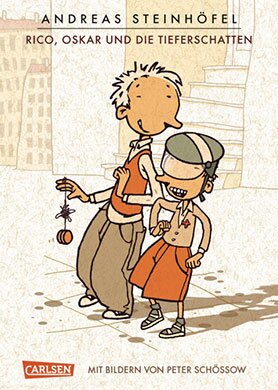

Andreas Steinhöfel

Rico, Oskar und die Tieferschatten

[Rico, Oskar and the shadow spooks]

- Carlsen Verlag

- Hamburg 2008

- ISBN 978-3-551-55551-9

- 224 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Andreas Steinhöfel

Rico, Oskar und die Tieferschatten

[Rico, Oskar and the shadow spooks]

Published in Portugiesisch (Bras.) with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

Review

Rico, Oskar and the Shadow Spooks by Andreas Steinhöfel, the acclaimed children’s author, is an original and witty detective story for the young reader. Rico, the sleuth and hero of the story, is from the Kreuzberg district of Berlin where he lives with his mother in ‘Dieffe 93’ – Dieffenbachstraße 93. At times things ‘rattle around in his head like a Bingo drum’. And he finds it hard to distinguish between left and right. Lucky that Dieffenbachstraße is such a long street with lots of shops, so that he doesn’t often need to take any turnings when doing an errand. Fortunately the walk to his school, the remedial learning centre on the Landwehr Canal, is also quite short. Yet Rico is anything but stupid. In this holiday diary he relates his view of things. And when one day his friend Oskar is kidnapped, he moves into top gear – he rescues him and what’s more, reveals the identity of the notorious ALDI kidnapper.

‘Dimwit’ is what Fitzke, the grumpy neighbour calls him. But Rico knows that’s wrong. ‘At this point I should explain that my name is Rico and I am a lowly gifted child. That is to say I do an awful lot of thinking, but it usually takes me a bit longer than other people. It’s not my brain - that’s quite a normal size. But sometimes a few things drop out, and unfortunately I never know beforehand from which part.’ That sounds reasonable. Altogether Rico has a very clear view of the world. He is shrewd and observant and gets to the bottom of things. Words he doesn’t know he asks to have explained to him or looks them up. And to prevent him forgetting them again, he writes them down. ‘The problem with unusual words is that they often have a very simple meaning, but some people like to complicate things.’

‘Depression’ is one of those words. Rico calls it the ‘grey feeling’ and explains it this way: ‘A depression is when all your feelings are sitting in a wheelchair. They’ve lost their arms and unfortunately there’s no one around to push them. And even the wheels might have flat tyres. Very tiring.’ He observes this ‘grey feeling’ in many people. In Frau Dahling, for example, who lives in the same block, works on the meat counter at Karstadt, and with whom he watches films in the evenings. She feels lonely since her husband cheated on her and she threw him out. Sometimes Rico also worries about his mother, after all it’s a long time since his father died. She’s bringing him up on her own, works in a bar at night and sleeps late. Sometimes she’s sad, then she takes Rico in her arms and they both have a little cry.

Rico knows his neighbours in ‘Dieffe 93’ very well. For example there’s the dishevelled and disagreeable Fitzke, the warm-hearted Frau Dahling, the Kessler family with lots of children, and the students, Jule, Massoud and Berts, who often have loud music blaring out from their flat. It’s the building at the back that Rico finds scary. It’s closed off as it’s been in danger of collapse ever since Fräulein Bonhöfer turned the gas on and killed herself. When Rico looks out of his window, he often catches sight of mysterious ‘shadow spooks’ there.

One day he meets Oskar on the stairs. Oskar is rather small, always wears a motorcycle helmet, so that all you can see under it are his large teeth, and has a small red airplane pinned to his T-shirt. A bit odd, thinks Rico. But Oskar is nice and highly gifted as well. The two of them, lowly gifted and highly gifted become friends. They suit each other well.

‘I’m nearly always in a good mood, but don’t know a lot. Oskar knew any amount of strange things, but he was always in the doldrums.’ Then one day his new friend doesn’t turn up where they had arranged to meet. It soon emerges that ’Mister 2000’, the child kidnapper who has had the city on tenterhooks for some time, has got hold of him. Rico is in no doubt – he’s going to find Oskar. But to do so he’ll have to overcome a few obstacles and fears …

Rico, Oskar and the Shadow Spooks is told throughout from the perspective of the young hero. Herein lies the strength of the book, for Rico’s view of things is extremely original. But in no way is it that of a ‘child with learning difficulties’, peculiar or disconcerting. Quite the contrary, it is an improvement on the everyday, conventional perspective. Rico’s perception of reality is surprising, but always comprehensible and furthermore distinctly astute. It comes as no surprise that the ‘lowly gifted’ investigator solves the riddle of the kidnapping.

What is more Rico is an exceptionally gifted storyteller. The words that Andreas Steinhöfel puts in the mouth of his protagonist are direct, powerful and original. For example he says ‘buzz’ instead of ‘booze’, and gives a logical explanation: booze is what alcoholics do which usually makes them talk rubbish’, so that their words just ‘buzz’ about. Many Berlin slang expressions also find their way into the book. The author has combined this freedom of expression with a story of virtuoso inventiveness. Both Rico and the inhabitants of ‘Dieffe 93’ emerge as fully rounded characters that are entirely credible. And there is no lack of suspense. No, neither Rico nor his readers need be afraid of that ‘grey feeling’.

‘Dimwit’ is what Fitzke, the grumpy neighbour calls him. But Rico knows that’s wrong. ‘At this point I should explain that my name is Rico and I am a lowly gifted child. That is to say I do an awful lot of thinking, but it usually takes me a bit longer than other people. It’s not my brain - that’s quite a normal size. But sometimes a few things drop out, and unfortunately I never know beforehand from which part.’ That sounds reasonable. Altogether Rico has a very clear view of the world. He is shrewd and observant and gets to the bottom of things. Words he doesn’t know he asks to have explained to him or looks them up. And to prevent him forgetting them again, he writes them down. ‘The problem with unusual words is that they often have a very simple meaning, but some people like to complicate things.’

‘Depression’ is one of those words. Rico calls it the ‘grey feeling’ and explains it this way: ‘A depression is when all your feelings are sitting in a wheelchair. They’ve lost their arms and unfortunately there’s no one around to push them. And even the wheels might have flat tyres. Very tiring.’ He observes this ‘grey feeling’ in many people. In Frau Dahling, for example, who lives in the same block, works on the meat counter at Karstadt, and with whom he watches films in the evenings. She feels lonely since her husband cheated on her and she threw him out. Sometimes Rico also worries about his mother, after all it’s a long time since his father died. She’s bringing him up on her own, works in a bar at night and sleeps late. Sometimes she’s sad, then she takes Rico in her arms and they both have a little cry.

Rico knows his neighbours in ‘Dieffe 93’ very well. For example there’s the dishevelled and disagreeable Fitzke, the warm-hearted Frau Dahling, the Kessler family with lots of children, and the students, Jule, Massoud and Berts, who often have loud music blaring out from their flat. It’s the building at the back that Rico finds scary. It’s closed off as it’s been in danger of collapse ever since Fräulein Bonhöfer turned the gas on and killed herself. When Rico looks out of his window, he often catches sight of mysterious ‘shadow spooks’ there.

One day he meets Oskar on the stairs. Oskar is rather small, always wears a motorcycle helmet, so that all you can see under it are his large teeth, and has a small red airplane pinned to his T-shirt. A bit odd, thinks Rico. But Oskar is nice and highly gifted as well. The two of them, lowly gifted and highly gifted become friends. They suit each other well.

‘I’m nearly always in a good mood, but don’t know a lot. Oskar knew any amount of strange things, but he was always in the doldrums.’ Then one day his new friend doesn’t turn up where they had arranged to meet. It soon emerges that ’Mister 2000’, the child kidnapper who has had the city on tenterhooks for some time, has got hold of him. Rico is in no doubt – he’s going to find Oskar. But to do so he’ll have to overcome a few obstacles and fears …

Rico, Oskar and the Shadow Spooks is told throughout from the perspective of the young hero. Herein lies the strength of the book, for Rico’s view of things is extremely original. But in no way is it that of a ‘child with learning difficulties’, peculiar or disconcerting. Quite the contrary, it is an improvement on the everyday, conventional perspective. Rico’s perception of reality is surprising, but always comprehensible and furthermore distinctly astute. It comes as no surprise that the ‘lowly gifted’ investigator solves the riddle of the kidnapping.

What is more Rico is an exceptionally gifted storyteller. The words that Andreas Steinhöfel puts in the mouth of his protagonist are direct, powerful and original. For example he says ‘buzz’ instead of ‘booze’, and gives a logical explanation: booze is what alcoholics do which usually makes them talk rubbish’, so that their words just ‘buzz’ about. Many Berlin slang expressions also find their way into the book. The author has combined this freedom of expression with a story of virtuoso inventiveness. Both Rico and the inhabitants of ‘Dieffe 93’ emerge as fully rounded characters that are entirely credible. And there is no lack of suspense. No, neither Rico nor his readers need be afraid of that ‘grey feeling’.

Translated by Alisa Jaffa

By Eva Kaufmann