Book World

Spring Literature 2025: Maximum Sensitivity for Today‘s World

The Leipzig Book Fair Prize was awarded for the 21st time on March 27. The prize is unique, challenging and unifying, not least because it is awarded in three categories: fiction, essays/non-fiction and translation. It is a reminder of the importance of reading, of engaging in serious discussions about texts, and of the artistry of words that make conversation possible in the first place. It also tells us something about the sensitivity of literature to the present moment; this beautiful, slow, old-fashioned and simultaneously hot medium that resonates widely, serves as a repository, and stimulates debate.

This year, the Leipzig Book Award for European Understanding, which traditionally opens the book fair, was awarded to Alhierd Bacharevič for his novel ”Dogs of Europe” (Voland & Quist), a book that was first celebrated in his homeland Belarus, but by the second printing was buried. The eloquent and wild saga, which is divided in six parts, takes us to Minsk, a Baltic island and to Berlin.

We can find a bit of solace these days in knowing that war only recently has become a ubiquitous event in human history. Archaeologist Harald Meller, historian Kai Michel and evolutionary biologist Carel van Schaik present this finding in their vividly co-written work: “Die Evolution der Gewalt“ (dtv). Their conclusion: waging war is not an integral part of human nature. We have long existed without war, and we are capable of doing so again. The award for the best non-fiction book this year went to Irina Rastorgueva for “Pop-up-Propaganda. Epikrise der russischen Selbstvergiftung“ (Matthes & Seitz Berlin). She shows us with relentless clarity how Putin’s propaganda machinery works: how lies, aggression and contradictions have destabilized Russian reality and replaced it with a nearly opaque house of mirrors. Many books are currently taking a look at the past and finding clear parallels to the present. One example is Jens Bisky’s clever and elegantly written study “Die Entscheidung: Deutschland 1929 bis 1934“ (Rowohlt), a polyphonic panorama in which politicians and journalists speak openly, as well as nationalists and social democrats, writers and lawyers. Bisky‘s meticulously researched book argues that the end of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Hitler did not unfold with the inevitability of a Greek tragedy. “Die Entscheidung“ is an astute and convincingly argued rejection of the conditions that had created the Weimar legacy. And a reminder to make the right decisions this time around. In philosopher Eva von Redecker‘s words: “We are used to losing the world: that is our way of living in it.” She reflects on the current state of affairs, while drawing our attention to the need for breaking old habits. This year‘s books articulate such a hope, while focusing on the environment, climate catastrophe and our relationship to nature. The star of the German climate activist scene Luisa Neubauer, for instance, asks: “What if we were brave?”, “Was wäre, wenn wir mutig sind?“ (Rowohlt), and opens our eyes to the power struggles and lobbyists behind the climate crisis. In her encouraging book she asks why we are so slow in rethinking our way of life. Jan Röhnert calls for a new form of nature writing. In “Wildnisarbeit” (Arco Verlag), he argues that this kind of writing cannot be accomplished by sitting at a desk alone. The author introduces us to people and their works that combine the act of writing about things that can only be experienced in the field. Meanwhile, a new volume in the Nature series published by Matthes & Seitz brings us closer to the “Birch Trees” (“Birken”) - an elegant and nonchalant invitation by author Steffi Memmert-Lunau to see these ubiquitous trees as saviors of the forest. According to her, they bring back biodiversity and counteract the destruction caused by climate change.

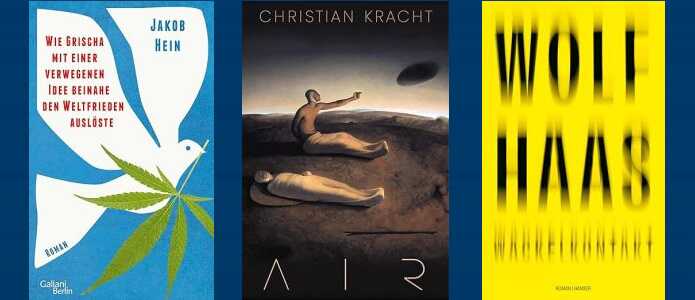

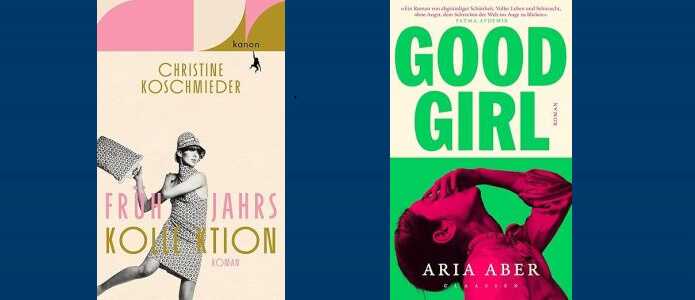

Writers place demands upon themselves and upon their readers, even if it means traversing a tricky aesthetic space. Both Christian Kracht‘s “Air” (Kiepenheuer & Witsch) and Wolf Haas‘ “Wackelkontakt” (Hanser), show great artistry and are exhilarating reads. The degree to which writing depicts one‘s own biography, and illustrates family constellations is demonstrated this year by the guest country Norway: Autofiction writers were represented in Leipzig by such big names as Karl Ove Knausgaard, Thomas Espedal and, above all, Vigdis Hjorth. A literature that deals with pain, but also with overcoming obstacles - contemporary German literature is second to none in this— is exemplified by the 70-year-old Helene Bracht in her debut novel: “Das Lieben danach” (Hanser). The text brilliantly breaks a taboo and is uniquely self-assured. The book deals with abuse - and its limits. Dmitrij Kapitelman is known for diving deeply into his novels, but with immense wit. In “Russische Spezialitäten” (Hanser Berlin), he takes us into the ‘Magasin’, a store in Leipzig that actually existed and had been owned by his parents. This was the place where the Eastern European diaspora met to reminisce about their homeland over kvass and pelmeni until Russia invaded Ukraine. The son cannot understand his mother’s continued support of Russia, whereas in Kristine Bilkau’s novel “Halbinsel” (Luchterhand) it is the daughter whose behavior is disconcerting. The trope of a child leaving her parents is reversed in this story. Though the daughter attempts to hide under her mother‘s wing, the mother has long since cut the chord between them. Kristine Bilkau was awarded the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in the fiction category for her literary exploration how to live ethically even in times of crisis. A mother-daughter relationship burdened by war-guilt plays an important role in Christine Koschmieder’s finely tuned novel „Frühjahrskollektion“ (Kanon Verlag), which delivers the clear message that fashion is always political. Finally, a very special book concludes the round-up of exemplary spring literature: Aria Aber with “Good Girl” (Claassen Verlag). The author with Afghan roots grew up in Germany, has lived in the USA for several years and is a star of the poetry scene there. She translated her debut novel from English into German. The book is located in the techno scene in Berlin around the 2010s. It tells the story of young Nila, as she sails through clubs, drug excesses, love affairs and everyday racism. It is a historiography of a city very close to our own times.

Nearly 300,000 people visited the Leipzig Book Fair from March 27-30. More visitors than ever before, and when I asked publishers about their impressions of the fair, they exclaimed “Leipzig is back!” and “Books are back!” I believe the fair‘s success and renewed interest in reading books arises from an urgent need for orientation, good ideas and exchange in times of crisis and war. The book fair combines both: a confrontation with— and escape from the world. Above all, it offers one of the few spaces of community in our divided society. Literature: this beautiful slow medium, literature that is sensitive to the present, but not in turmoil over the present, can show us ways to liberate ourselves from old habits and help prevent history from repeating itself.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

Copyright: © 2025 Litrix.de