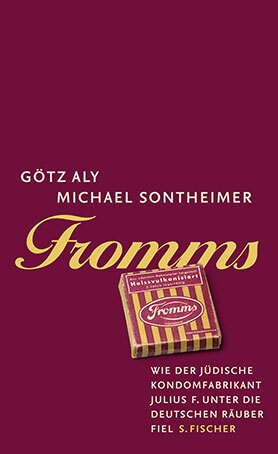

Götz AlyMichael Sontheimer

Fromms

[Fromms] – Wie der jüdische Kondomfabrikant Julius F. unter die deutschen Räuber fiel [How the Jewish Condom Manufacturer, Julius F., Got Robbed by the German Thieves]

- S. Fischer Verlag

- Frankfurt am Main 2007

- ISBN 978-3-10-000422-2

- 244 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Götz Aly

Michael Sontheimer

Fromms

[Fromms]

Sample translations

Review

“The minor stories--not infrequently dreadful and only discovered by chance--which even our archivists miss in their guidebooks directed toward fame and sensation, are what make the writing of history so gratifying.”

And it is precisely one of these minor stories that Götz Aly and Michael Sontheimer have rescued from forgetting and given us access to: the story of the Jewish condom manufacturer Julius Fromm, the founder and owner of one of “those Jewish enterprises which perished in the Nazi period and have been almost completely ignored by historians.”

The authors combine the economic history of the business with the history of the Fromm family which, hoping for a better life, left the Russian town of Konin for Berlin in 1893. That’s how Israel (later Julius) Fromm, at that time ten years old, made it from the Jewish ghetto of a town shaped by poverty and piety to Berlin’s Scheunenviertel, the most impoverished and disreputable part of the city. At first the family survived by rolling cigarettes, but Julius wanted more. Having taught himself the chemistry of rubber processing, in 1914 at the age of 30 he founded a one-man company to manufacture of rubber goods. He apparently had a sense for the right product at the right time, because in the First World War the demand for condoms rose enormously. By making crucial improvements, Fromm created the first brand-name condom in 1916, a product that he vouched for with his own name.

With the constant increase in production, it became necessary to expand the business as well. The new factory building of 1930 was well lit, practical and very up to date with its Bauhaus-style architecture. Its standards in terms of working conditions went far beyond the usual ones of the time.

The history of Julius Fromm is one of ascent, but it’s also about the integration and defiance of a man who did not wish to see himself as a victim in times of rising anti-Semitism. His assimilation almost reached the point of self-denial. In 1933 Fromm let a swastika flag wave in his company’s commissary and encouraged both of his managers to join the Nazi party. His condoms were now promoted as “triumphant first-glass products.” He could not imagine that he, a patriotic entrepreneur and good taxpayer would simply be driven away. But all of his accommodations proved to be in vain: even his business finally fell victim to “Aryanization.” In 1938, Julius Fromm was forced to sell his factory for a song to Göring’s godmother.

Even though he had hesitated for a long time in the face of ongoing harassment to leave the country for good, he managed to get himself and most members of his family to London and exile at the last minute.

The history of this business is additionally a good illustration of how Jewish companies in the “Third Reich” were plundered both by the state and by individuals, of how “Aryanization” and corruption in this period were linked.

These days there is very little information left about Julius Fromm. Important sources such as the company archives and estate papers have been lost. The book can therefore be little more than a silhouette. Aly and Sontheimer conducted interviews with some of the relatives of Julius Fromm who are still alive. But the largest part of the story is provided by official documents from the “Third Reich.” In the book’s second half, Julius Fromm is hardly an active figure at all anymore. In this way, even the narrative illustrates the inactivity to which Fromm was condemned after his escape, as the Nazis in Germany gradually appropriated his fortune in elaborate bureaucratic maneuvers.

What starts in the form of anecdotes, ends by necessity in the detailed reconstruction of net assets. Aly and Sontheimer increasingly permit the numbers to speak for themselves. The description of account transactions, the uncommented enumeration of ownership structures shows how enormous the plundering was. In this way, the depicted of the injustice committed becomes almost unbearable. Aly and Sontheimer meticulously reconstruct how the assets left behind by Fromm were “socialized.” His bank assets were incorporated as war bonds for the Reich Treasury. His Berlin mansion in the Rolandstrasse was passed on to a recipient of the Knight’s Cross in 1943, following the deportation and murder of his relatives who still remained. The household furnishings were publicly auctioned, from costly furniture to simple housewares: “national comrades” became sale shoppers. In his book Hitlers Volksstaat, Aly has already portrayed how the expropriation of the Jews by the Nazi regime was seen as a legitimate means for propping up the nation’s budget. The plundering of Fromm’s property is a significant example for this, the fate of an individual showing the workings of Hitler's “dictatorship of accommodation.” “Julius Fromm fell victim to thieves. Yet he did not fall victim to a heap of bandits, but to a state and its citizens.” That’s how the authors sum it up. They estimate that the expropriation of Fromm at today’s prices be valued about 30 Million Euros.

The GDR did not want to see Fromm as a victim of the Nazi regime, but as a “capitalist exploiter,” classifying his rubber works as the “asset of a war criminal“ so as to turn it into a state-owned enterprise. And West Germany refused in 1962 to pay compensation for what it called “leaving furniture behind.”

Julius Fromm didn’t have to experience that any more. He died in 1945, just few days after the war’s end, in London, where until the end he had preserved the hope of being able to return to production in his factory one day soon.

And it is precisely one of these minor stories that Götz Aly and Michael Sontheimer have rescued from forgetting and given us access to: the story of the Jewish condom manufacturer Julius Fromm, the founder and owner of one of “those Jewish enterprises which perished in the Nazi period and have been almost completely ignored by historians.”

The authors combine the economic history of the business with the history of the Fromm family which, hoping for a better life, left the Russian town of Konin for Berlin in 1893. That’s how Israel (later Julius) Fromm, at that time ten years old, made it from the Jewish ghetto of a town shaped by poverty and piety to Berlin’s Scheunenviertel, the most impoverished and disreputable part of the city. At first the family survived by rolling cigarettes, but Julius wanted more. Having taught himself the chemistry of rubber processing, in 1914 at the age of 30 he founded a one-man company to manufacture of rubber goods. He apparently had a sense for the right product at the right time, because in the First World War the demand for condoms rose enormously. By making crucial improvements, Fromm created the first brand-name condom in 1916, a product that he vouched for with his own name.

With the constant increase in production, it became necessary to expand the business as well. The new factory building of 1930 was well lit, practical and very up to date with its Bauhaus-style architecture. Its standards in terms of working conditions went far beyond the usual ones of the time.

The history of Julius Fromm is one of ascent, but it’s also about the integration and defiance of a man who did not wish to see himself as a victim in times of rising anti-Semitism. His assimilation almost reached the point of self-denial. In 1933 Fromm let a swastika flag wave in his company’s commissary and encouraged both of his managers to join the Nazi party. His condoms were now promoted as “triumphant first-glass products.” He could not imagine that he, a patriotic entrepreneur and good taxpayer would simply be driven away. But all of his accommodations proved to be in vain: even his business finally fell victim to “Aryanization.” In 1938, Julius Fromm was forced to sell his factory for a song to Göring’s godmother.

Even though he had hesitated for a long time in the face of ongoing harassment to leave the country for good, he managed to get himself and most members of his family to London and exile at the last minute.

The history of this business is additionally a good illustration of how Jewish companies in the “Third Reich” were plundered both by the state and by individuals, of how “Aryanization” and corruption in this period were linked.

These days there is very little information left about Julius Fromm. Important sources such as the company archives and estate papers have been lost. The book can therefore be little more than a silhouette. Aly and Sontheimer conducted interviews with some of the relatives of Julius Fromm who are still alive. But the largest part of the story is provided by official documents from the “Third Reich.” In the book’s second half, Julius Fromm is hardly an active figure at all anymore. In this way, even the narrative illustrates the inactivity to which Fromm was condemned after his escape, as the Nazis in Germany gradually appropriated his fortune in elaborate bureaucratic maneuvers.

What starts in the form of anecdotes, ends by necessity in the detailed reconstruction of net assets. Aly and Sontheimer increasingly permit the numbers to speak for themselves. The description of account transactions, the uncommented enumeration of ownership structures shows how enormous the plundering was. In this way, the depicted of the injustice committed becomes almost unbearable. Aly and Sontheimer meticulously reconstruct how the assets left behind by Fromm were “socialized.” His bank assets were incorporated as war bonds for the Reich Treasury. His Berlin mansion in the Rolandstrasse was passed on to a recipient of the Knight’s Cross in 1943, following the deportation and murder of his relatives who still remained. The household furnishings were publicly auctioned, from costly furniture to simple housewares: “national comrades” became sale shoppers. In his book Hitlers Volksstaat, Aly has already portrayed how the expropriation of the Jews by the Nazi regime was seen as a legitimate means for propping up the nation’s budget. The plundering of Fromm’s property is a significant example for this, the fate of an individual showing the workings of Hitler's “dictatorship of accommodation.” “Julius Fromm fell victim to thieves. Yet he did not fall victim to a heap of bandits, but to a state and its citizens.” That’s how the authors sum it up. They estimate that the expropriation of Fromm at today’s prices be valued about 30 Million Euros.

The GDR did not want to see Fromm as a victim of the Nazi regime, but as a “capitalist exploiter,” classifying his rubber works as the “asset of a war criminal“ so as to turn it into a state-owned enterprise. And West Germany refused in 1962 to pay compensation for what it called “leaving furniture behind.”

Julius Fromm didn’t have to experience that any more. He died in 1945, just few days after the war’s end, in London, where until the end he had preserved the hope of being able to return to production in his factory one day soon.

Translated by David A. Brenner

By Patrizia Loacker