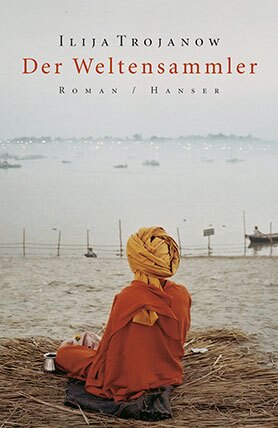

Ilija Trojanow

Der Weltensammler

[The world collector]

- Carl Hanser Verlag

- Munich 2006

- ISBN 978-3-446-20652-6

- Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Ilija Trojanow

Der Weltensammler

[The world collector]

Published in Portugiesisch (Bras.) with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

Review

It is hard to imagine a better tale: the real-life story of the British officer Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821 – 1890) who trekked across entire continents, knew India, Arabia and Africa like the back of his hand, was one of the first Europeans to visit the holy sites of Mecca and Medina, and otherwise experienced countless adventures. Inspired by Burton’s life and the writings he left behind, the author Ilija Trojanow, born in Sofia in 1965, has now written a lavish novel about this World Collector – as the book is entitled. Yet much more than a spectacular collection of splashy events, this novel is truly a remarkable achievement

It would appear that in Trojanow Burton has found a congenial brother, since the author, of Bulgarian descent, is himself a globetrotter. In 1971 he was forced to flee with his family via Yugoslavia and Italy to Germany, where they were granted asylum. However, he grew up in Kenya and later returned to Munich to study law and cultural anthropology in the mid-80s. In Munich he also started two publishing houses, the first in 1989, and the second in 1991. In 1999 he moved to Bombay and now lives in Cape Town. He writes in German, and this so splendidly that the present novel was awarded the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in 2006. Even in his first novel “Die Welt ist groß und Rettung lauert überall” [The World is Big and Salvation is Waiting Around Every Corner] Trojanow proved himself to be a bracing story-teller capable of interweaving with utmost composure a multitude of vibrant scenes and stories into one compelling piece of literature.

Fortunately, in his World Collector Trojanow does not succumb to the obvious temptation of (re)creating Burton’s larger-than-life biography as garishly as possible. For even as a young man Burton was working in Persia and India as an operative. He traveled as an Arabian merchant through Somalia and as an Afghani doctor through Arabia. He was the first European to reach Lake Tanganyika, traveled across America and, in his later years, completed a critical translation of Thousand and One Nights and the Kama Sutra. The officer was, moreover, a true linguistic genius, learning thirty languages along the way. Talk about the basis for a novel! Yet what else can an author add to it? Trojanow surveys his material well and isolates three episodes from the life of his hero: his years spent on the Indian subcontinent, his ensuing voyage to Mecca, and, finally, his African expedition to the source of the Nile.

Trojanow’s decision to tell each of these episodes from a slightly different perspective proves to be a clever narrative device. Whereas the novel’s first part is largely comprised of the memoirs of Burton’s servant Naukaram, the second part unfolds as Burton’s travelogue. Then, in the third part, Burton’s tales are meshed with the oral reports of his slave.

As soon as the officer arrives in the British West Indies upon his trip from England, he makes a charming deal with the Indians, trading port wine for vocabulary. And as his servant reports, Burton learns quickly, taking lessons in Sanskrit from a Brahmin and becoming acquainted with the great spiritual diversity of the land. In this section Trojanow creates what may be the most memorable passages of his novel. There is hardly another author who has captured so directly the oppressive, overly crowded, and painfully multifarious and cacophonous atmosphere of Bombay: “The bounteous city belched at times. Everything smelled as if decomposed by stomach acids. At the side of the road lay sleep, half-digested and about to melt away.” In Trojanow’s nuanced depictions the reader can almost feel the noise of the markets, the whispers of the traders and prostitutes, and the odors of the houses and the streets.

The middle section of the novel is chiefly devoted to the tenacity with which Burton seeks to attain his goals. He converted to Islam, on the one hand, to show his respect for Islamic culture, but, on the other hand, also to be able to visit the holy sites of Mecca and Medina which, at the time, were off limits to infidels. In the third long chapter of the novel, seen through the eyes of another travel companion, the slave Sidi Mubarak Bombay, we follow Burton along his privation-riddled expedition to be the first person to reach the source of the Nile.

With its many different narrative strands, the book’s great strength lies, nonetheless, in the author’s avoidance of constructing mere folklore, complete with a lurid stage of figures draped in exotic costumes. By means of the historical novel Trojanow persuasively addresses the essence of what it means to be foreign, of the possibilities and strategies of adopting foreign cultures without completely destroying their unique qualities. Through the refined use of altering perspectives – India as seen through the eyes of an Englishman juxtaposed with the bewildered reactions of India’s inhabitants upon meeting the English gentleman – and the many encounters Trojanow interweaves during Burton’s travels in Africa and Arabia, foreignness turns out to be nothing more than a contrivance of those who travel abroad for the first time.

It would appear that in Trojanow Burton has found a congenial brother, since the author, of Bulgarian descent, is himself a globetrotter. In 1971 he was forced to flee with his family via Yugoslavia and Italy to Germany, where they were granted asylum. However, he grew up in Kenya and later returned to Munich to study law and cultural anthropology in the mid-80s. In Munich he also started two publishing houses, the first in 1989, and the second in 1991. In 1999 he moved to Bombay and now lives in Cape Town. He writes in German, and this so splendidly that the present novel was awarded the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in 2006. Even in his first novel “Die Welt ist groß und Rettung lauert überall” [The World is Big and Salvation is Waiting Around Every Corner] Trojanow proved himself to be a bracing story-teller capable of interweaving with utmost composure a multitude of vibrant scenes and stories into one compelling piece of literature.

Fortunately, in his World Collector Trojanow does not succumb to the obvious temptation of (re)creating Burton’s larger-than-life biography as garishly as possible. For even as a young man Burton was working in Persia and India as an operative. He traveled as an Arabian merchant through Somalia and as an Afghani doctor through Arabia. He was the first European to reach Lake Tanganyika, traveled across America and, in his later years, completed a critical translation of Thousand and One Nights and the Kama Sutra. The officer was, moreover, a true linguistic genius, learning thirty languages along the way. Talk about the basis for a novel! Yet what else can an author add to it? Trojanow surveys his material well and isolates three episodes from the life of his hero: his years spent on the Indian subcontinent, his ensuing voyage to Mecca, and, finally, his African expedition to the source of the Nile.

Trojanow’s decision to tell each of these episodes from a slightly different perspective proves to be a clever narrative device. Whereas the novel’s first part is largely comprised of the memoirs of Burton’s servant Naukaram, the second part unfolds as Burton’s travelogue. Then, in the third part, Burton’s tales are meshed with the oral reports of his slave.

As soon as the officer arrives in the British West Indies upon his trip from England, he makes a charming deal with the Indians, trading port wine for vocabulary. And as his servant reports, Burton learns quickly, taking lessons in Sanskrit from a Brahmin and becoming acquainted with the great spiritual diversity of the land. In this section Trojanow creates what may be the most memorable passages of his novel. There is hardly another author who has captured so directly the oppressive, overly crowded, and painfully multifarious and cacophonous atmosphere of Bombay: “The bounteous city belched at times. Everything smelled as if decomposed by stomach acids. At the side of the road lay sleep, half-digested and about to melt away.” In Trojanow’s nuanced depictions the reader can almost feel the noise of the markets, the whispers of the traders and prostitutes, and the odors of the houses and the streets.

The middle section of the novel is chiefly devoted to the tenacity with which Burton seeks to attain his goals. He converted to Islam, on the one hand, to show his respect for Islamic culture, but, on the other hand, also to be able to visit the holy sites of Mecca and Medina which, at the time, were off limits to infidels. In the third long chapter of the novel, seen through the eyes of another travel companion, the slave Sidi Mubarak Bombay, we follow Burton along his privation-riddled expedition to be the first person to reach the source of the Nile.

With its many different narrative strands, the book’s great strength lies, nonetheless, in the author’s avoidance of constructing mere folklore, complete with a lurid stage of figures draped in exotic costumes. By means of the historical novel Trojanow persuasively addresses the essence of what it means to be foreign, of the possibilities and strategies of adopting foreign cultures without completely destroying their unique qualities. Through the refined use of altering perspectives – India as seen through the eyes of an Englishman juxtaposed with the bewildered reactions of India’s inhabitants upon meeting the English gentleman – and the many encounters Trojanow interweaves during Burton’s travels in Africa and Arabia, foreignness turns out to be nothing more than a contrivance of those who travel abroad for the first time.

Translated by Jeff Tapia

By Oliver Jahn