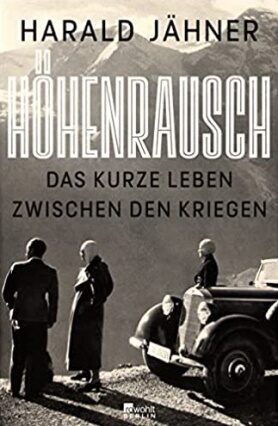

Harald Jähner

Höhenrausch. Das kurze Leben zwischen den Kriegen

[Exhilaration – The Short Life Between the Wars]

- Rowohlt Buchverlag

- 2022

- ISBN 978-3-7371-0081-6

- 560 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Sample translations

Intoxication and Sobriety in Interbellum Berlin

In Exhilaration: The Short Life Between the Wars, Harald Jähner, the former editor of the culture section of the Berliner Zeitung newspaper and an award-winning narrative history author, has taken a closer look at everything in during the interbellum Germany that created the intoxicating and unsettling sense of existing a historical turning point. The result is a virtuosic work of phenomenology, thematically organized, anecdotal, sharp-witted and as tautly written as a topical novel in which the moral, technological, political and erotic intermingle and create previously unknown constellations.

In the new Germany that emerged between the wars, everything was, well, new. And most often the new was faster than before. This was true of everything from transportation, telecommunications and the press to dance crazes, in which, thanks to the shimmy, dancing evolved into something no longer for couples but for individuals, particularly females, who wanted to live life to the fullest.

Everything new in this period came about quickly, including emancipatory processes, which were of course above all a big-city phenomenon. Social mobility in Germany was never more pronounced than in 1920s Berlin, where unmarried young women from the working classes suddenly had a new range of future opportunities as telephone operators and secretaries. In those functions, Jähner writes, they got to know the customs of educated people: “They didn’t ladle their soup from lunchpails like these women’s proletarian brothers. They ate with colleagues in spacious canteens or had standing reservations in their favorite restaurants.” Jähner adds, “At home these women were the ones who read out loud and explained official government letters to their parents.”

Still, Jähner is aware of the ambivalence of this phenomenon. Emancipated young big-city secretaries were one side of the coin; the first platforms for institutional sexism were the other. “Office life buzzed with physical attraction and dreams of social betterment, but it was also poisoned by cynical exploitation, scheming and tragic love affairs.” While the “new woman” became a fashionable buzzword among well-educated female members of the bourgeoisie, women like Erika Mann, Clärenore Stinnes or Maria Therese Hammerstein who raced around in sports cars, ´low-level office workers emancipated themselves in Berlin’s countless dancehalls. Here flappers wore flat shoes and pageboy or even masculinely short hairstyles. Commensurately, the tempo of the new dance steps was double that of those from previous eras. Some observers saw in this the demise of bourgeois culture.

Jahner’s panoramic depiction of the epoch is also fascinating in those aspects that seem to directly align with our own timers. There are numerous parallels with today: the back and forth between militarism, revolution and vengefulness and the difficulties of achieving reconciliation under a political leadership largely devoid of charisma. “It was a burden ‘not to know where you belonged’ and ‘just to living through one’s days,’ when so many of your fellow citizens were being inflamed by rampant visions of salvation,” writes Jähner, citing the indecisive hero of Siegfried Kracauer’s topical novel Georg.

With great virtuosity, Jähner connects the concerns of intellectuals beset with melancholy to the social philosophy of Helmuth Plessner. Plessner’s 1924 The Limits of Community remains a fascinating analysis of human behavior in anonymous urban society, in which the main issue is the proper distance between individuals who need to move through the urban hustle and bustle, not too far away from and not to close to others. Plessner saw atomized society, much to the dismay of those on the political Right, as no longer a community but an agreeable plurality. That was why the liberal concept of society became a point of attack for right-wing theories. “In a community, cohesion is defined in terms of ancestry and common values, in a society, in terms of rules governing the interactions of people potentially unknown to one another.” Jähner also cites an aphoristic saying from the cultural theorist Helmut Lethen: “When transport becomes a central issue, beings who long to put down roots will feel ill at ease.”

That analysis also perfectly fits the excitable tenor of interbellum Germany. Euphoric enthusiasm for technology and modern dystopia, upward social mobility and the dramatic decline of those left behind, spectacular flights of human reason and nonsense spouted by muddled minds went hand in hand in the Weimar Republic. How it turned out is common knowledge, but Harald Jähner retells the story for an audience that includes those who would put the spirit of liberalism back into the one-way bottle from whence it never actually came. That spirit, as Jähner’s book shows, is the product of the rumbling, rotating society between the wars.

Translated by Jefferson Chase

By Katharina Teutsch

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic. She writes for newspapers and magazines such as: the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Tagesspiegel, die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and for Deutschlandradio Kultur.

Publisher's Summary

Fifteen years that are like a century – an exciting new look at the short period between the wars.

Germany 1918. The end of the First World War, revolution and the victory of democracy sees, at the same time, the triumph of a more liberated way of life. Everything is supposed to fundamentally change: the “new woman”, the “new man”, the “new living” and the “new thinking”. When the economy begins to see an upward trend in the mid-1920s, Germany becomes a different country. Women conquered the race tracks and tennis courts, went out alone at night, cut their hair short and didn’t even think about getting married. Jähner describes the emergence of hobbies; boxing; dance halls (hotspots of the new era); offices and city traffic; department stores promising happiness; and the streets as the site of bitter conflict. So much of it seems strikingly modern. The taste for irony, sincerity and directness. But also, the fear of the “debasement of all values”, the ascendancy of things that are cheap. A large proportion of Germans did not identify with this emergence. Over time, it was clear that there was a deep division in society and that this could not be tolerated.

Harald Jähner delivers an overall portrayal of this pulsating, rich era as it has never been seen before – and depicts the image of a divided country full of violent and shocking energies. It is disturbingly similar to the way we are now and yet – hopefully – completely different.

(Text: Rowohlt Buchverlag)