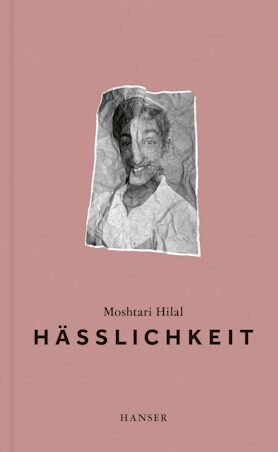

Moshtari Hilal

Hässlichkeit

[Ugliness]

- Carl Hanser Verlag

- Munich 2023

- ISBN 978-3-446-27682-6

- 224 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Published in Italian with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

Ugliness as Revolt

This also applies to racist categories related to having: “too” dark skin color, “too” much body hair, or - particularly popular among twentieth-century racial theorists - a “too” big nose. Biometric pseudoscience had made a name for itself already in the 19th century with Cesare Lombroso. The Italian doctor believed he could define and identify criminals on the basis of measurable physical characteristics. Moshtari Hilal reminds us of the long and catastrophic history of modern physiognomy, which emerged around the same time as eugenics, and which decades later led to an unprecedented policy of annihilating “worthless lives.” In other words, those lives that had been labeled as being ugly. But even in the democratic 21st century, the face remains a “hermeneutic surface” that constantly is being read. The global beauty industry enjoys a lucrative business as a result of it. Nowadays technology, aided by filters and facial poses, are shared millions of times and are used as a means to propagate a new ideal face that often fetishizes a variety of ethnic features.

Hilal argues that today’s means of measuring facial geometries, enhanced by social media filters, is reminiscent of the biometric excesses of the notorious racial theorists of the past.

In five associatively structured chapters, the author reminds us that the definition of ugliness always begins with hatred of deviance. In an autobiographical mode, she focuses on rhinoplasty—a surgical remodeling of the nose—which a Jewish doctor, of all people, had used as a common remedy for the so-called “Jewish nose”. During the Nazi regime, “Nose Joseph,” as Jacques Joseph was called by his fellow plastic surgeons, had lost his license to practice.

Hilal introduces us to her four sisters, all of whom were born with a nose that was considered too large. In contrast to their decision to operate, Hilal consciously refused to adapt her nose to Western ideals of beauty. She describes her reason for the decision thusly: “When my eldest sister had her nose operated on, I felt as if my family had been castrated.” The definition of beauty, Hilal writes, usually involves a fantasy that denigrates any deviation from the ideal face, ideal hair, ideal skin color, thus reinforcing the norm of an elite minority.

The anti-colonial theorist Franz Fanon argued that the ideal of beauty, which had been established by white colonial society, led to the colonial subject’s alienation from their self. “The oppressor, through the comprehensive and terrifying character of his authority, manages to impose new ways of seeing on the indigenous people and, in particular, a pejorative judgement of their original forms of existence.” Hilal reminds her readers of the systematic representation of the colonized body as being either criminal, barbaric, or weak. In her words: “Whiteness structures people’s desires, feelings, bodies and minds. The perception that one’s own skin is wrong creates an unbearable sense of being imprisoned, a uniform that never can be removed.”

In the late 1970s, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu reminded us that the production of taste has always been part of a symbolic class struggle. She traces the vast popularity of rhinoplasty in Iran to racially motivated images of the body, and the desire to identify oneself within a growing Iranian middle class that wants its “good face” to be read as a sign of class, economic success and urbane modernity. In other words: racist power relations find their direct expression in what is commonly perceived as beautiful or ugly.

Moshtari Hilal interlaces her book with self-portraits that are artfully modified along with lyrical self-explorations that focus on large female noses and black body hair. Her playful and versatile approach to ugliness as a label invites readers to liberate themselves of preconceived notions. By scrutinizing one’s own ideals of beauty, and by tracing the transformation of these ideals over the years, we are better able to identify the power relations hidden within these structures. In the end, it becomes clear that is the attribution of ugliness, not ugliness itself, that is driven by hatred of the other.

Translated by Zaia Alexander

By Katharina Teutsch

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic. She writes for newspapers and magazines such as: the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Tagesspiegel, die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and for Deutschlandradio Kultur.

Publisher's Summary

»I observed beautiful, successful women whom I wanted to be like and whom my mother and aunts were not like.«

Every ideal form of beauty is profoundly political – nowhere is this more obvious than in our approach to ugliness

In this evocative, tightly-woven text, Hilal creates a unique hybrid, merging her essay with visual references

Poetic and touching, intimate and highly political, Moshtari Hilal talks about us all when she talks about the norms we subject ourselves to. How do power and beauty join forces, and determine who is considered ugly? What role does ugliness play in hatred? Dense body hair, brown teeth and big noses: Moshtari Hilal questions ideas of ugliness – ostensibly her own, but in fact, all of ours. In this unique book, she writes about beauty salons in Kabul as a backdrop to the US invasion, Darwin’s theory of evolution, Kim Kardashian and a utopian place in the shadow of her nose. Her explorations, analyses, memories, visual references and own drawings take the reader into the most intimate realms, putting self-image to the test. Why are we afraid of ugliness?

(Text: Carl Hanser Verlag)