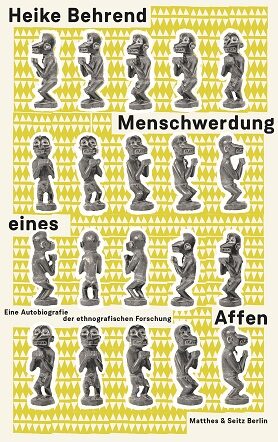

Heike Behrend

Menschwerdung eines Affen. Eine Autobiografie der ethnografischen Forschung

[Incarnation of an Ape. An autobiography of ethnographic research]

- Matthes & Seitz Verlag

- Berlin 2020

- ISBN 978-3-95757-955-3

- 278 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

Published in Italian with a grant from Litrix.de.

Sample translations

How an Ethnologist Became an Ape

One possible explanation is that Behrend does several things at once in her book. For starters, she provides a cogent history of her discipline with copious examples that proceeds from its humble beginnings as “armchair ethnology” to the heroes of participant observation before moving on to her own experiences in the field. The insight Behrend repeatedly takes away from her work that the Other is not the only alien in the equation. The researcher herself is also an alien to those she’s observing.

Bronislaw Malinowski, Franz Boas and Margaret Mead are all important names in this discipline, whose participant investigations contributed greatly to the field, moss prominently by liberalizing how ethnologists conceived the Other. Nevertheless, as Behrend points out, the relationship between researcher and researched is always hierarchical. Modern Western social science seeks out contact pre-modern ritual and its protagonists for the purpose of describing them as objects.

Behrend herself worked for decades on various cultural phenomena: the possession cults of Uganda, photographic practices in East Africa, and the understanding of time in the Kenyan Tugen Hills. Her ambition was to follow in the footsteps of the ethnographic greats with their seminal studies. But whereas the pioneers of field research wrote with the heroic gesture of scholars triumphantly returning from alien situations, Behrens described the dead ends into which her “will to knowledge” maneuvered her. In the late 1970s, as a doctoral student, she went to Africa to pursue the ideal of a "salvation anthropology," a search for a form of authentic originality beyond modernity. But once in the field, she saw through the ideal of the primordial as a romantic notion. "In the early 1980s," Behrend writes, "ethnologists began to comprehend that they had not only 'altered' African societies, making them more exotic than they were. Scholars had also located them in a prehistoric era and thus (...) denied that they existed simultaneously with themselves in the same space. They stamped African societies to be traditional and pre-modern, even though they were integrated in the global capitalist world order at the latest since the transatlantic slave trade."

Over the course of her own research projects, Behrend was forced to realize that she had no control over either the object of her research or even her own self-image. Because of her long, flowing hair and ignorance of local standards of decency, the inhabitants of Tugen Hills mocked her for a long time as an ape. “I had to admit that not only my hair but my whole person was considered ugly,” she writes. The trope of the ape, she added, bounced back and forth between the colonists and the colonized in the long history of the colonial encounters. In this case, it was the ethnologist who appeared as an ape in the eyes of the Other, whom she was trying to describe.

Still, she was an “ape with the possibility of promotion.” In time, Berend earned the respect of her host community and was allowed to take part in its various rituals of initiation. At no point, however, did her research belong entirely to her. Those being ethnographically described had their own agenda. The village elders, for instance, were only so forthcoming because their authority was threatened by the advances of modernity in Africa, which hadn’t halted before the Tugen Hills. Interest shown by one of the most important institutions of western modernity, the university, was a useful tool for propping up those elders’ power. This general self-interest influenced much of the “information” they provided.

Whereas her personal interactions with the people of the Tugen Hills only somewhat threatened her as an ethnologist, years later in Uganda, Behrend had to completely give up any notion of objective ethnography. While researching the possession cults in that country at the height of the AIDS crisis, which included tracking down supposed cannibals, Behrend experienced three things: the brutalization of the phenomenon under the influence of the Catholic Church; her own stigmatization as a suspected cannibal, notwithstanding all her assurances that cannibalism didn’t exist in Europe; and the sudden global notoriety of the murderer Armin Meiwes, the so-called “cannibal of Rothenburg.”

Behrend offers readers a comprehensible biography of an academic discipline amidst constant experimentation. In the 1980s, after all, scholars began thinking critically about intercultural appropriation. The resulting perspectives continue to inform contemporary discussions about things like restoring looted cultural artefacts and outmoded attitudes in classic children’s books.

Today, the role of the observer and the observed is included as a matter of curse in research questions. In his seminal 1929 study The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia, Malinowski promoted the idea that the ethnographer was an expert on his alien society. By the 1990s, an anthology entitled The Sexual Life of Anthropologists delivered a riposte to that presumption. And the sex life of anthropologists, writes Behrendt with a sigh, was pretty desolate.

Among other things it is thanks to such refreshing modesty, that Behrend’s book emerges so prominently from this year’s non-fiction. Heike Behrend earned a doctorate from the Free University of Berlin in the late 1980s with a dissertation on the sense of time among the people of the Tugen Hills. She sent a copy to her interpreter Naftali Kipsang, who for a long time didn’t answer. “But then a letter arrived in which he tanked me for the book. He wrote that there had been a terrible drought in the Tugen Hills, with every living thing there going hungry, so a goat had eaten my book.”

By Katharina Teutsch

Katharina Teutsch is a journalist and critic. She writes for newspapers and magazines such as: the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Tagesspiegel, die Zeit, PhilosophieMagazin and for Deutschlandradio Kultur.

Publisher's Summary

Heike Behrend studied ethnology in the politically turbulent 1960s; her first field research took her to the Kenyan Tugen Mountains in the late 1970s; in the mid-1980s she set out on the trail of the Holy Spirit movement in northern Uganda. During the AIDS epidemic, she worked through the Catholic Church in western Uganda, and finally, on the Kenyan coast, she researched the local practices of street photographers and photo studios. This autobiography of ethnographic research does not tell a heroic success story, but rather reports on what is usually excluded in traditional ethnographies - the unheroic entanglements and cultural misunderstandings, the conflicts and situations of failure in foreign countries. This book thus invites a frank look at ethnology as a poetics of social relations. In the unflattering names - „monkey,“ „fool,“ or „cannibal“ - given to the ethnologist in Africa, she is confronted with foreign experience of foreign countries and must ask herself what truth these names express, what colonial history they tell, and what criticism they make of her person and work. With her report on four ethnographic research projects in Kenya and Uganda over a period of almost fifty years, Heike Behrend also reflects on the specialist history of ethnology and the changes in the power relations between the researchers and the explored, which she experiences first-hand.

(Text: Matthes & Seitz Verlag)