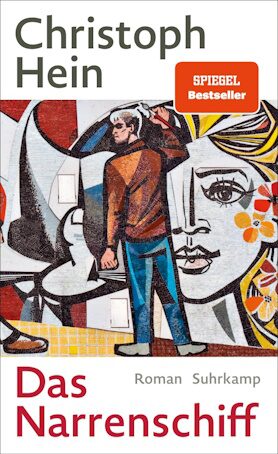

Christoph Hein

Das Narrenschiff

[Ship of Fools]

- Suhrkamp Verlag

- Berlin 2025

- ISBN 978-3-518-43226-6

- 750 Pages

- Publisher’s contact details

For this title we provide support for translation into the Polish language (2025 - 2027).

Sample translations

No Zero Hour

Hein is no ideologue and no firebrand. Though he typically writes from the perspective of so-called ordinary people, nothing could be further from his style than cheap populism. Now, at the age of over 80, Hein has produced his most expansive novel to date, nearly 800 pages long. Das Narrenschiff can be read as a magnum opus – an epic novel in prose. And the novel, paradoxically, proves two things. First: Christoph Hein is not a natural stylist, nor does he pretend to be. Second: he is a great writer all the same – perhaps even because of this. His storytelling is direct, his eye for the telling detail sharp. Grounded in deep knowledge and attuned to subtle shifts in mood, Hein traces the arc of the GDR from beginning to end. And even if readers feel they’ve heard it all before, they’re still likely to find enormous pleasure in this book.

The title Das Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools) is a nod to Sebastian Brant’s 1494 moral satire, here turned towards the socialist state. Asked about the title in an interview with Der Spiegel, Hein replied: “What else could it have been called? The GDR’s economic policy rested on the belief that you could abolish inflation by decree. Prices were artificially fixed at 1944 levels – whether for a bread roll or a flat. That was never going to work. It was folly. Pure stupidity.” To render the collapse convincingly, Hein shifts perspective in Das Narrenschiff. This time, his protagonists aren’t everyday citizens but members of the GDR nomenklatura – people tied to the system in various ways, some of whom were later cast out by it.

The novel opens with Wilhelm Pieck, the Republic’s founding president, visiting a primary school and meeting a girl named Kathinka. Her family story becomes the novel’s thread. Kathinka’s father was murdered by the National Socialists; her new stepfather, Johannes Goretzka, climbs the Party ladder until he contradicts central planning targets and is demoted. Her mother, Yvonne, is appointed head of Berlin’s cultural institutes thanks to her husband’s connections – despite having no idea what the role involves. But she adapts. And here, adapting means learning to operate within the system while quietly carving out room for herself.

Das Narrenschiff is a novel of lofty plans, quiet compromise and pragmatic betrayal; of ambition, self-denial and the politics of survival. It is also a reminder that there was never such a thing as a true “zero hour” in either East or West Germany. Again and again in the book, experts challenge the Party’s planned economy, knowing full well its goals are unrealistic or absurd. Again and again, people are appointed to roles they are unfit for – like the distinguished Anglicist Benaja Kuckuck, who fails every ideological test in both German states and ends up working as a censor for children’s films. Hein’s irony lies in presenting such absurdities without comment, letting his characters bring them to life through startlingly vivid dialogue. It’s this method – lifelike scenes interwoven with historical narrative – that gives Das Narrenschiff its clarity and conviction. The novel is history told through fiction, in the best sense.

Hein himself appears in the novel too, indirectly. Kathinka is based on his late wife, the director and dramaturge Christiane Hein, who died in 2002. It is her family’s story he tells. When he, a student of mathematics and philosophy who goes by the name Rudolf Kaczmarek in the novel, is introduced to Kathinka’s parents, he declares matter-of-factly that, as an agnostic, he believes only in what can be proven beyond doubt. “The same goes for utopias, promises of salvation, and visions of the future. They may or may not be realistic – we keep our distance.” It’s a pragmatic stance, and one that Christoph Hein has held onto into old age.

Translated by Alexandra Roesch

By Christoph Schröder

Christoph Schröder, born 1973, lives and works as a freelance author and reviewer in Frankfurt am Main. Among others, he writes for ZEIT, Deutschlandfunk and SWR Culture.

Publisher's Summary

A sweeping, epochal novel about life in East Germany

A state is founded, like all states, for eternity, but disappears after forty years, almost without a trace. Are the people who once lived there condemned to oblivion, their dreams just a brief breeze in the great winds of history?

In his sparking social novel, Christoph Hein brings men and women together who, upon the founding of the German Democratic Republic, are assigned the most diverse roles. He accompanies them through the dramatic developments of a nascent society, which strives to be the better Germany and yet stumbles from one failure to the next.

Card-carrying communists, formerly fanatic Nazis, functionaries caught up in imbroglios, intellectuals trying to salvage their bourgeois lifestyles under real existing socialism, shoe salesmen, waiters, factory workers, building superintendents, and even a high-ranking Stasi agent recognise, in one way or another, their membership in an involuntary crew on board a social vessel that they increasingly come to view as a ship of fools, and whose course is verging ever nearer to the menacing cliffs of history.

(Text: Suhrkamp Verlag)